Does your firm have enough cash on an ongoing basis to meet its operational obligations? This is an important indication of financial health. Liquidity ratios provide information about a firm’s ability to meet its short-term financial obligations. They are of particular interest to those extending short-term credit to the firm. Investors often take a close look at liquidity ratios when performing fundamental analysis on a firm. Since a company that is consistently having trouble meeting its short-term debt is at a higher risk of bankruptcy, liquidity ratios are a good measure of whether a company will be able to comfortably continue as a going concern.

Two frequently-used liquidity ratios are the current ratio (or working capital ratio) and the quick ratio.

Current Ratio

The current ratio indicates a company’s ability pay off its short-term debt using assets that can be easily liquidated. The current ratio measures whether or not a firm has enough resources to pay its debts over the next 12 months. Potential creditors use this ratio in determining whether or not to make short-term loans. The current ratio can also give a sense of the efficiency of a company’s operating cycle or its ability to turn its product into cash.

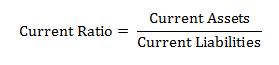

The current ratio is the ratio of current assets to current liabilities:

The current ratio measures your ability to meet short term obligations with short term assets, a useful indicator of cash flow in the near future.

A Firm needs to ensure that it can pay its salaries, bills and expenses on time. Failure to pay loans on time may limit your future access to credit and therefore your ability to leverage operations and growth.

A ratio less that 1 may indicate liquidity issues. A very high current ratio may mean there is excess cash that should possibly be invested elsewhere in the business or that there is too much inventory. Most believe that a ratio between 1.2 and 2.0 is sufficient.

The one problem with the current ratio is that it does not take into account the timing of cash flows. For example, you may have to pay most of your short term obligations in the next week though inventory on hand will not be sold for another three weeks or account receivable collections are slow.

Short-term creditors prefer a high current ratio since it reduces their risk. Shareholders may prefer a lower current ratio so that more of the firm’s assets are working to grow the business. Typical values for the current ratio vary by firm and industry. For example, firms in cyclical industries may maintain a higher current ratio in order to remain solvent during downturns. One drawback of the current ratio is that inventory may include many items that are difficult to liquidate quickly and that have uncertain liquidation values.

Quick Ratio

The quick ratio is an alternative measure of liquidity that does not include inventory in the current assets. The quick ratio is a measure of a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations using its most liquid assets (near cash or quick assets). Quick assets include those current assets that presumably can be quickly converted to cash at close to their book values. Quick ratio is viewed as a sign of a company’s financial strength or weakness; it gives information about a company’s short term liquidity. The ratio tells creditors how much of the company’s short term debt can be met by selling all the company’s liquid assets at very short notice.

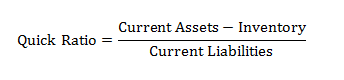

The quick ratio is defined as follows:

The current assets used in the quick ratio are cash, accounts receivable, and notes receivable. These assets essentially are current assets less inventory. The quick ratio is often referred to as the acid test.

Cash Ratio

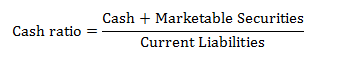

The cash ratio is the most conservative liquidity ratio. It excludes all current assets except the most liquid: cash and cash equivalents. The cash ratio is defined as follows:

The cash ratio is an indication of the firm’s ability to pay off its current liabilities if for some reason immediate payment were demanded. It is a more stringent liquidity test that indicates if a firm has enough short-term assets (without selling inventory) to cover its immediate liabilities.

This is often referred to as the “acid test” because it looks at the company’s most liquid assets only (excludes inventory) that can be quickly converted to cash. A ratio of 1:1 means that a firm can pay its bills without having to sell inventory

Which ratio is a better measure of a firm’s short-term position?

In some ways, the quick ratio is a more conservative standard. If the quick ratio is greater than one, there would seem to be no danger that the firm would not be able to meet its current obligations. If the quick ratio is less than one, but the current ratio is considerably above one, the status of the firm is more complex. In this case, the valuation of inventories and the inventory turnover are obviously critical.

A number of problems with inventory valuation can contaminate the current ratio. An obvious accounting problem occurs because organizations value inventories using either of two methods, last in, first out (LIFO) or first in, first out (FIFO). Under the LIFO method, inventories are valued at their old costs. If the organization has a substantial quantity of inventory, some of it may be carried at relatively low cost, assuming some inflation in overall prices. On the other hand, if there has been technical progress in a market and prices have been falling, the LIFO method will lead to an overvalued inventory. Under the FIFO method of inventory valuation, inventories are valued at close to their current replacement cost. Clearly, if we have firms that differ in their accounting methods, and hold substantial inventories, comparisons of current ratios will not be very helpful in measuring their relative strength, unless accounting differences are adjusted for the computations.

A second problem with including inventories in the current ratio derives from the difference between the inventory’s accounting value, however calculated, and its economic value. A simple example is a firm subject to business-cycle fluctuations. For a firm of this sort, inventories will typically build during a downturn. The posted market price for the inventoried product will often not fall very much during this period; nevertheless, the firm finds it cannot sell very much of its inventoried product at the so-called market price. The growing inventory is carried at the posted price, but there is really no way that the firm could liquidate that inventory in order to meet current obligations. Thus, including inventories in current assets will tend to understate the precarious financial position of firms suffering inventory buildup during downturns.

Might we then conclude that the quick ratio is always to be preferred? Probably not. If we ignore inventories, firms with readily marketable inven¬tories, appropriately valued, will be undeservedly penalized. Clearly, some judicious further investigation of the marketability of the inventories would be helpful.

Low values for the current or quick ratios suggest that a firm may have difficulty meeting current obligations. Low values, however, are not always fatal. If an organization has good long-term prospects, it may be able to enter the capital market and borrow against those prospects to meet current obligations. The nature of the business itself might also allow it to operate with a current ratio less than one. For example, in an operation like McDonald’s, inventory turns over much more rapidly than the accounts payable become due. This timing difference can also allow a firm to operate with a low current ratio. Finally, to the extent that the current and quick ratios are helpful indexes of a firm’s financial health, they act strictly as signals of trouble at extreme rates. Some liquidity is useful for an organization, but a very high current ratio might suggest that the firm is sitting around with a lot of cash because it lacks the managerial acumen to put those resources to work. Very low liquidity, on the other hand, is also problematic.

Working Capital

Working Capital is a measure of cash flow and should always be a positive number. It measures the amount of capital invested in resources that are subject to quick turnover. Lenders often use this number to evaluate your ability to weather hard times. Many lenders will require that a certain level of Working Capital be maintained. It is defined as follows: