Theresa May, the UK’s new prime minister, explained

Theresa May, the UK’s home secretary, will be the country’s next prime minister. Her final rival for the Conservative Party leadership, Andrea Leadsom, withdrew from the race on Monday morning, citing overwhelming support for May among Conservative MPs. Prime Minister David Cameron then announced that he would formally resign by Wednesday, ushering May into the top job.

May’s tenure will not be easy. She’ll be taking over at time of intense crisis: The Brexit referendum has thrown the UK into what one expert calls “its worst political crisis since May 1940.” It’s not an exaggeration to say that May’s tenure will shape the course of British and European history for the foreseeable future.

Understanding May — who she is, and what drives her — is critical to understanding the events that will unfold in the next months and years. So here’s a quick guide to the next occupant of 10 Downing Street — where she’s coming from politically, what she’s said about Brexit, and why she may be facing an impossible dilemma as the UK’s next leader.

May is a fairly moderate conservative — except on immigration

Since May’s election to Parliament in 1997, she’s taken fairly liberal stances on a number of social issues. She made a name for herself in 2002, when she delivered a speech telling her fellow Conservatives that they need to stop being the “nasty party” in UK politics.

She’s an avowed feminist: She led a fight to close the UK’s gender wage gap in 2008 and frequently confronts sexist comments about her fondness for stylish shoes.

“To the extent that May’s political credo is evident, she is a liberal Conservative,” the Financial Times’s George Parker and Helen Warrell wrote in a 2014 profile. She’s “supportive of gender equality, champion of female representation at Westminster and a backer of gay marriage.”

But her record doesn’t always fit the “liberal” description: For instance, she twice voted against legalizing adoption by gay couples in the early 2000s. This is especially true when it comes to immigration.

Since 2010, May has served as home secretary, the UK’s top social and domestic Cabinet post. During her time in office, she has repeatedly expressed vociferous opposition to the UK’s historically high immigration levels.

“When immigration is too high, when the pace of change is too fast, it’s impossible to build a cohesive society,” she said in one 2015 speech. “It’s difficult for schools and hospitals and core infrastructure like housing and transport to cope. And we know that for people in low-paid jobs, wages are forced down even further while some people are forced out of work altogether.”

None of this is true — the data shows that immigrants haven’t stressed the UK economy and in fact have contributed to its growth. But that hasn’t stopped May from taking some fairly draconian steps to lower immigration.

Most infamously, May used her power as home secretary to impose a rule that would block skilled immigrants from permanently settling in the UK if they made less than £37,000 a year (roughly $53,000 at pre-Brexit exchange rates). Anyone who made less than that would be deported. May’s own Home Office estimated that the rule could cost the British economy more than $200 million, but she went through with it anyway.

May’s tenure as Home Secretary was also particularly unpleasant for LGBTQ migrants.

“Aderonke Apata, an LGBT rights activist from Nigeria, was told by Home Office lawyers who rejected her asylum claim last March that she could not be a lesbian because she had children. May described Apata’s fight against deportation as a ‘publicity stunt,’” Dawn Foster writes at the London Review of Books. This was not an isolated incident, Foster explains:

Time and again during May’s tenure at the Home Office, people fleeing countries where homosexuality is illegal were asked to explain why they didn’t ‘look lesbian’ or why they didn’t attend local Pride marches; others were subjected to extensive invasive questioning about their sex lives; some even felt compelled to provide documentary evidence of their sexuality.

In a certain sense, then, this makes May the right person for a post-Brexit Britain. The campaign for leaving the European Union was dominated by anti-immigrant rhetoric: EU rules required the UK to accept migrants from any other country inside the EU, which was unpopular with a huge number of Britons. Indeed, polling data suggests that anti-immigrant sentiment was the single most decisive factor in Britain voting to leave.

An anti-migration vote begat an anti-migration prime minister.

May opposed Brexit weakly and politically — and now will have to deal with the terrible fallout

Given May’s high-profile stance on immigration, you might have expected her to have been a vocal supporter of the campaign to leave the EU. Interestingly, she wasn’t. In fact, May was the only major candidate for Conservative leadership who supported remaining.

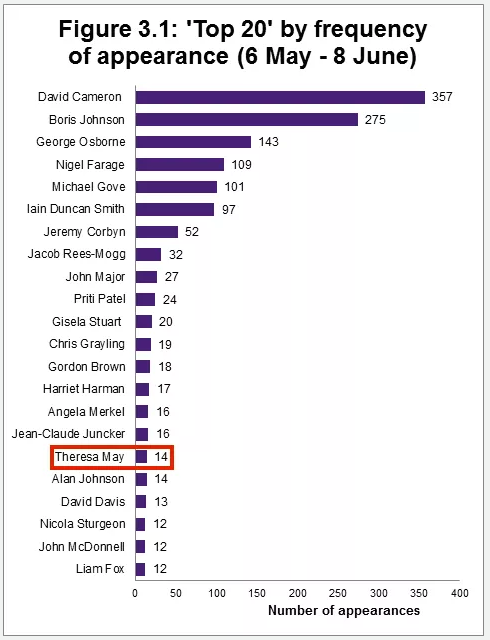

Her support, however, was pretty lukewarm. The UK’s Loughborough University tallied up the number of statements to the press on Brexit made by leading political figures between early May and early June, a critical pre-vote period. It found that May made a tiny number of appearances — far fewer than most similarly famous UK politicians, and even fewer than the German chancellor, Angela Merkel:

British political observers saw this as a calculated strategy: May would formally side with the Conservative leadership in opposing a Brexit (that is, a British exit) but take a lukewarm stance in order to remain politically palatable to Brexiteers in the event that the “Leave” campaign won.

“This could all be part of Mrs May’s plan: to cast herself as the Brexit-friendly Remainer who can appeal to her colleagues in the Out camp with her toughness on immigration,” the Telegraph’s Asa Bennett wrote before the vote. “Her restrained approach to campaigning for Remain has helped her avoid alienating Tory [Conservative Party] Brexiteers, and the polls suggest her reputation has held up better than some of her potential leadership rivals.”

Indeed, May’s pandering to the Brexit crowd continued after the vote — and in much more impactful ways.

You see, the Brexit referendum actually wasn’t a binding vote. In order for the UK to actually exit the EU, the British government has to formally submit notification under Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union. Cameron refused to do that, saying it would be up to his successor to manage the transition. That left open the possibility that his successor would choose not to submit Article 50 notification either, essentially nullifying the Brexit vote.

But May has repeatedly promised not to do that, with “Brexit means Brexit” being something of a catchphrase during her leadership campaign. “As prime minister, I will make sure we will leave the European Union,” May said on Monday, per the BBC. She promised there would be “no attempts to remain inside the EU” nor “attempts to rejoin it by the backdoor.”

That’s pretty unequivocal.

However, she has also pledged not to trigger Article 50 immediately upon taking the top job. She wants the UK to wait until at least the end of the year, in an attempt to negotiate terms with the EU that would preserve British access to European markets without having to allow unfettered immigration.

“We shouldn’t invoke Article 50 immediately,” she said in one interview. “What’s important for us is that we get the right deal.”

The problem, however, is that the EU leadership is unlikely to agree to any such deal. They don’t want to reward Britain’s vote with favorable exit terms, for fear that voters in other countries (like Greece, France, or the Netherlands) will take this as a sign that they could get a similar deal. So far, EU leaders have been adamant that May’s “right deal” won’t be on offer.

So unless May can change the EU leadership’s mind, she’s in a pretty impossible position. Either she unilaterally exits the EU without a deal, which would tank the British economy by cutting off access to vital EU markets, or she goes back on her own promise that “Brexit means Brexit,” which would likely be political suicide.

It’s a very, very tough way for the UK’s second female prime minister to start off her job — and one that might just set her up for failure.

Source: Vox – Theresa May, the UK’s new prime minister, explained

This is typical of caMoron’s disgusting mismanagement of the British Government as the traitor he is to Queen and Country. This woman will not be any better. In fact, it seems as though he was waiting for a mug like her to drop his incredible mess upon and she is not consistent with her ideas anymore than he was. in fact, you could say you smelt a rat in the making. I feel sorry for Britain as it was once the World’s greatest leader in times of conflict but this pair will cripple the country beyond repair. It’s all about making the rich richer and denying the poor their right to any expectations at all.