The Sterner, Stricter SEC

As Mary Jo White sees it, the Securities and Exchange Commission’s job is to patrol Wall Street and Main Street and catch financial fraudsters. Since becoming the agency’s chair in April 2013, White, a former federal prosecutor and defense attorney, has repeatedly stressed that the agency will get tougher on financial crime and that, as she said in October 2013, “the SEC is, in very important part, a law enforcement agency.”

For some CFOs, that characterization conforms exactly with how they think of the 80-year-old securities regulator. But it’s “not the way the SEC thought of itself in years past,” says Stephen Crimmins, a former senior SEC enforcement official and now a partner at K&L Gates. “It thought of itself as a regulator that also did very important enforcement work. But increasingly, over the last 10 or 20 years, we’ve seen a much greater focus on enforcement as part of the SEC’s program.”

That focus has sharpened considerably in the wake of the financial crisis and Bernard Madoff’s massive Ponzi scheme. Former chair Mary Schapiro brought record numbers of enforcement actions in her tenure. And White, in her short time, has tried to boost the image of an SEC that is the country’s toughest cop on the financial markets beat. She’s adopted a “broken windows” philosophy of deterrence that emphasizes no offense is too small to ignore. In addition, she has repeatedly stated that the SEC is determined to step up its pursuit of corporate wrongdoers.

The success of those efforts, however, is very much to be determined. Much will depend on whether the agency can gain the resources it wants from an ever-parsimonious Congress.

Focus on Fraud

With the winding down of cases stemming from the financial crisis, White wants the SEC to focus more on accounting fraud. The agency’s Financial Reporting and Audit Task Force, created in July 2013, has the goal of “fraud detection and increased prosecution of violations involving false or misleading financial statements and disclosures,” according to the SEC. To detect accounting irregularities, the task force has at its disposal a quantitative tool called the Accounting Quality Model, aka “RoboCop.” (For more on the AQM, see “In Search of Suspect Accounting,” CFO, March.)

The ability of RoboCop to spot earnings fraud efficiently is unknown. Still, it is a step forward that the SEC is also taking a more systematic approach to fraud identification than it has in the past, says Dan Mahoney, director of research at forensic accounting research firm CFRA. “In the past, it was the decentralized offices finding fraud in the areas that they cover,” he says. “Now [the SEC] is taking a more top-down approach, coming up with best practices and using new technology to identify red flags and companies to target.”

At this point, though, the SEC is playing catch-up with earnings manipulators. A 2012 Duke University/CFO magazine survey, for example, found that a majority of CFOs believe that earnings management and shady accounting techniques go largely undetected, for significant periods of time. The crackdown on accounting fraud actually comes when the number of such cases has been steadily falling, along with the number of restatements. In fiscal 2013 the SEC brought 68 enforcement actions concerning financial fraud or issuer disclosure, the sixth straight year of decline and the lowest number in years.

There is no clear evidence of what’s causing the drop. But even the SEC’s director of enforcement, Andrew Ceresney, doesn’t believe the falloff is due to Sarbanes-Oxley and better internal controls at corporations, an observation some have made. Instead, Ceresney has implied that much fraud is still flying under the agency’s radar screen.

“The incentives are still there to manipulate financial statements,” Ceresney said in a speech last September. “Our view is that we will not know whether there has been an overall reduction in accounting fraud until we devote the resources to find out.”

Fessing Up

If the SEC can’t catch more companies in its net, it may be able to wring some public confessions out of the wrongdoers it does catch. That’s because the SEC is adopting a new admission-of-misconduct policy. The agency’s longstanding “neither-admit-nor-deny” policy, whereby companies settle charges without admitting or denying wrongdoing, has been criticized for being insufficiently deterrent.

Rejecting a $285 million SEC settlement with Citigroup in 2011, federal judge Jed Rakoff commented that Wall Street viewed such settlements “as a cost of doing business.” Says Brian Fox, president of Confirmation.com, an audit confirmation site: “Historically, I’ve gotten frustrated with the ability for somebody who’s committed fraud to basically pay a fine and then sign the statement that says they do not admit or deny any wrongdoing. It was kind of a ‘pay the fine and get out of jail free’ card.”

Under the new policy, the SEC will insist on an admission of misconduct in cases involving “particularly egregious conduct or widespread harm to investors,” as White said in an October 2013 speech at Fordham University. Elsewhere she explained that the agency would also require a company to admit wrongdoing in cases in which the conduct posed a significant risk to the market or investors; the admission would aid investors deciding whether to deal with a particular party in the future; or reciting unambiguous facts would send an important message to the market about a particular case.

But how often will the SEC be able to force a fraudster to admit he or she caused harm? After all, it may take much more resources to build an ironclad case that forces the perpetrators to admit defeat. And the SEC will still use its neither-admit-nor-deny policy, an important tool in the enforcement arsenal because, the agency says, it allows for higher settlements and faster relief for victims.

Mary McAllister Shepro, of Notre Dame Law School, argues in favor of the admission policy, concluding in an April 2014 paper that it “has the potential to bring the Commission’s ‘swagger back’ and deter violations of the securities laws. The consequences of admitting guilt are severe, and guilty defendants will be stuck between a rock and a hard place: admit guilt and face the collateral consequences” — such as shareholder lawsuits — “or litigate and face costly extralegal consequences and the possibility of losing at trial.”

Noting that less than 2% of SEC enforcement actions brought since June 2013 have required admissions of wrongdoing, Shepro predicts that the “approach should limit the number of trials the SEC actually has to bring (i.e. not be as costly as critics argue), while still procuring the benefits of requiring admissions of wrongdoing (i.e. social stigmatism for egregious violators).”

Money Talks

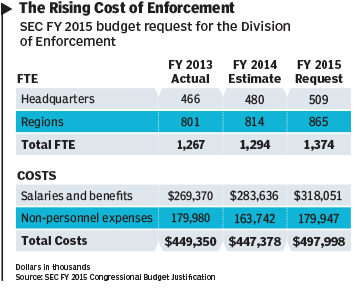

Will the SEC receive the additional resources it says it needs to crack down on accounting fraud and tighten up cases against all kinds of financial tricksters? White is asking Congress for $1.7 billion in funding for fiscal year 2015, up from $1.35 billion last year. Of that request, nearly $500 million would be earmarked for the Division of Enforcement.

Michael Piwowar, an SEC commissioner since August 2013, says the agency’s enforcement staff is “doing a fantastic job given the task they’ve been handed.” “Every week we have commission meetings and vote on cases,” Piwowar says. “We’re getting the cases from a number of sources, whether it’s our own compliance people identifying it, whether it’s a tip [or] referral, or a complaint we’re getting from someone in the industry, a whistle-blower. We’re seeing a wide variety of cases.”

But attorney Crimmins says improvements at the SEC will be difficult unless the agency gets more money. “People say, ‘Well, gosh, hasn’t [the SEC’s] budget gone up over the last decade or so?’ And of course it’s gone up in dollar terms, but in reality, relative to the mission, it’s crazy how underfunded it is,” he says. “The securities industry and the public companies that it regulates have exploded dramatically in terms of size and what the SEC needs to do to appropriately regulate them.”

In its Congressional Budget Justification for fiscal year 2015, the SEC notes the challenges facing the Enforcement Division. For example, the agency’s whistle-blower program has produced more than 6,500 tips through fiscal 2013, resulting in several large rewards. But the thousands of tips streaming in require people to vet them and investigate promising leads. Meanwhile, the aforementioned admission policy will result in additional litigation when defendants refuse to acknowledge wrongdoing. Overall, the agency says it needs more attorneys, forensic accountants, IT professionals, staff members, and technology to be the tough cop on the beat White wants it to be.

“We recognize that we cannot literally be on every corner, looking over the shoulder of every trader, or watching each CFO as they certify their financial results,” conceded White last October. “But we can allocate our resources in such a way so that market participants understand we are at least looking and pursuing charges in all directions.”

Authors: Marielle Segarra is a reporter at public radio station WHYY in Philadelphia. Edward Teach is editor-in-chief of CFO.

Source: cfo