What’s happening in the labour market?

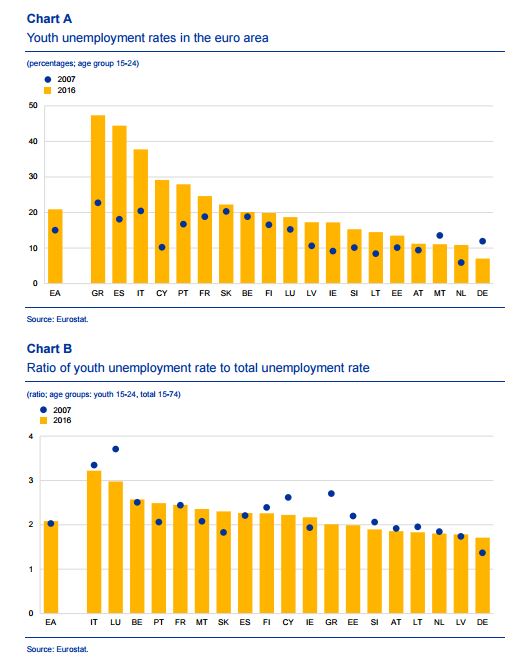

The rate of youth unemployment peaked at above 24% in the euro area in 2013 for the age group 15-24. Since then, the youth unemployment rate has declined faster than the total unemployment rate and remained around 21% in 2016, about 6 percentage points higher than in 2007. Against this background, this box describes some key recent features of youth unemployment across the euro area countries.

A close monitoring of developments in youth unemployment is necessary in view of potential scarring effects of unemployment, especially at the beginning of one’s career.1 Long periods of unemployment at a young age can result in increased risks of future unemployment, human capital losses and lower earnings. Youth unemployment rates are normally higher than total unemployment rates, but large differences across countries point to potential problems with labour market functioning in some countries.

Youth unemployment in the euro area remains above its pre-crisis level, but the ratio of youth unemployment to total unemployment has hardly changed. Youth unemployment is particularly high in Greece, Spain and Italy, following sharp rises during the crisis (Chart A). However, in spite of the very high youth unemployment rates, the ratio of youth unemployment to total unemployment did not change significantly between 2007 and 2016, which suggests that youth unemployment has moved in line with total unemployment (Chart B). Thus the very high levels of youth unemployment during the crisis reflect both the intensity of the crisis and relatively high youth unemployment in the pre-crisis period. In this regard, it is worth noting the large heterogeneity across countries. While for the euro area as a whole, the youth unemployment rate is 2.2 times higher than the total unemployment rate, in Italy and Luxembourg it is more than 3 times higher. By contrast, the youth unemployment rate in Germany is only about 1.7 times higher than the total unemployment rate.

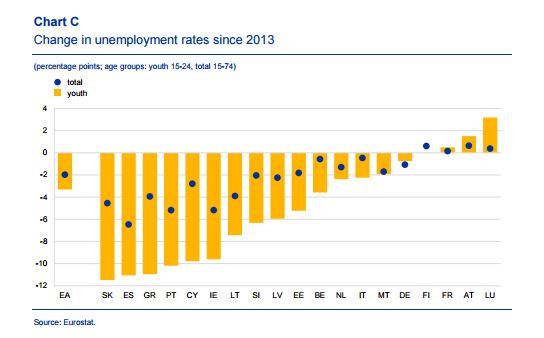

The youth unemployment rate is declining faster than the total unemployment rate, reflecting its higher sensitivity to the cycle. Between 2007 and 2013 the youth unemployment rate in the euro area increased by about 9 percentage points. In the same period, the total unemployment rate increased by about 4.5 percentage points (i.e. half as much as youth unemployment). Similarly, during the recovery, youth unemployment has been declining faster than total unemployment. Between 2013 and 2016, the youth unemployment rate declined by about 3.5 percentage points, while the total unemployment rate decreased by about 2 percentage points (Chart C). Slovakia, Greece and Spain – followed by Portugal, Ireland and Cyprus – are among the countries with the largest reductions in youth unemployment. In Greece and Spain, the declines in unemployment rates were accompanied by declines in participation rates.2

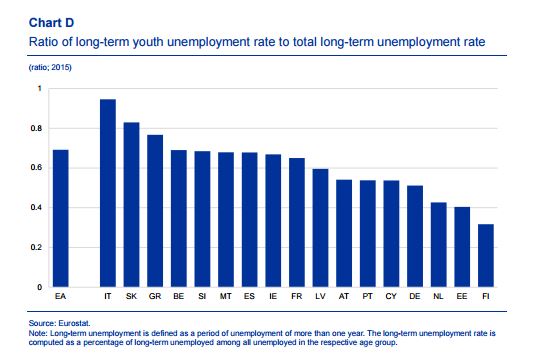

The share of young unemployed remaining unemployed for more than a year is lower than the share of total unemployed doing so. As expected, the share of young people that remain unemployed for more than one year is smaller than the corresponding figure for total unemployed, reflecting the fact that young people are more prone to intermittent transitions between activity and inactivity (e.g. to acquire further education or training). However, in some countries the share for young unemployed is close to the share for total unemployed (Chart D).

Overall, the relationship between youth unemployment and total unemployment has not changed since the crisis, but the high costs associated with youth unemployment indicate the need for policy measures to improve labour market functioning in some countries. Such policy measures include: (1) improving the quality and the labour market relevance of education, including via well-developed apprenticeship systems; (2) ensuring a well-functioning and responsible wage setting system, including when setting minimum wages; (3) enhancing the role of public employment services and the provision of active labour market policies with a view to supporting the unemployed during labour market transitions and increasing their employability; (4) increasing working time flexibility in order to facilitate a combination of work and education and to ease the transition from education to employment in the labour market.

1 See, for instance, Arulampalam, W., “Is Unemployment Really Scarring? Effects of Unemployment Experience on Wages”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 111, No 475, 2011, pp. 585-686.

2 There was a general decline in youth participation during the crisis. At the same time, the share of young people who are not in education or training and also not looking for jobs has remained relatively stable since 2007, leading to the conclusion that the decline in participation during the crisis reflects decisions to stay in or return to education.

Source: ECB