Explaining the credit cycle

This article summarises why the credit cycle leads to alternate booms and slumps. It is only with this in mind that they can be properly understood as current economic conditions evolve.

The reader is taken through three monetary models: a fixed money economy, one governed by changes in bank credit, and finally the consequences of central bank intervention.

Classical economics provided the basis for an understanding of the effects of bank credit expansion. The theory, embodied in the division of labour, eluded Keynes, who was determined to justify an interventionist role in the economy for the state.

Neo-Keynesian policies have been responsible for growing monetary intervention. This article serves as a reminder of the distortions introduced by the credit cycle and why central bank monetary policies are fundamentally destructive of the settled economic order that exists without monetary expansion.

Defining the problem

The credit cycle drives the business, or trade cycle. It should be obvious that changes in the quantity of money, mostly in the form of bank credit, has an effect on business conditions. Indeed, that is why central banks implement a monetary policy. By increasing the quantity of money in circulation and by encouraging the banks to lend, a central bank aims to achieve full employment. Other than quantitative easing, the principal policy tool is management of interest rates on the assumption that they represent the “price” of money.

But there is also a cyclical effect of boom and bust, linked to changes in the availability of bank credit, and so modern central banks have tried to foster the boom and avoid the slump.

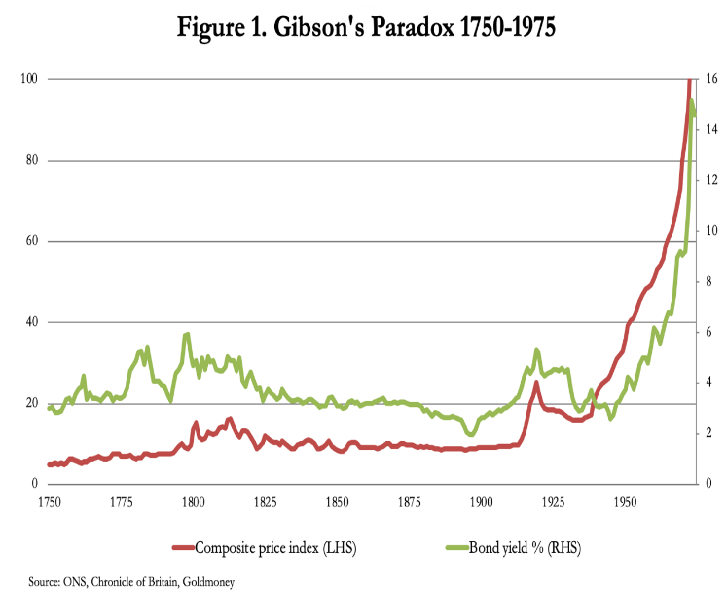

This is the Holy Grail for interest rate policy. Assuming interest is the price of money, there should therefore be a correlation between changes in interest rates and changes in the general price level. In other words, managing interest rates should allow a central bank to manage the general level of prices, and therefore, so it is said, influence the level of consumer demand. But empirical evidence denies this. The little-known Gibson’s paradox proves that there has been no such correlation, and instead, it is the price level and nominal interest rates that correlate, as shown in Figure 1 below, which is of Britain’s experience, covering a period of 225 years of relatively free markets.

The bond yield is of Consols undated stock, which with little variation acts as an effective proxy for wholesale borrowing costs, since it lacks the pull of a gross redemption yield.

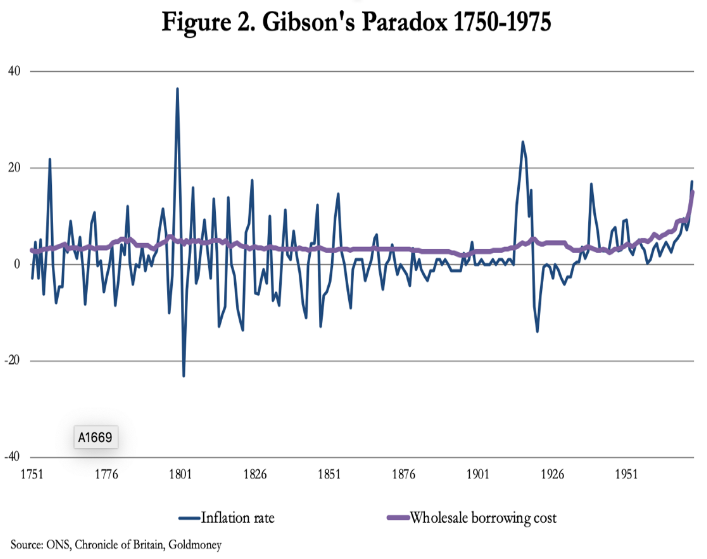

Contrast the correlation in Figure 1 with the lack of correlation in Figure 2, which shows no correlation between wholesale borrowing costs and the rate of price inflation.

Keynes, no less, named the phenomenon as a paradox in 1930, confirming the observations of Thomas Tooke in 1844 and then the eponymous Alfred Gibson, who wrote about it in an article for Banker’s Magazine in 1923. But because no one, including luminaries such as Keynes himself, Irving Fisher, Milton Friedman, and even Knut Wicksell, the Swedish economist who is remembered for his pioneering work on interest rates, managed to crack the paradox.

The solution of Gibson’s paradox turns out to be very simple, and I wrote a paper on it for Goldmoney in 2015. A businessman, allocating capital for the manufacture of a product, in his calculations had an important point of reference that could not be ignored: the price for which he might expect to sell his product. If the price was trending higher, he could afford to pay a higher rate of interest, the converse also being true. This tendency would be particularly marked if the expected profit for his product was experienced by other manufacturers, in other words the general level of prices was rising. Then we would find that the increased demand for monetary capital would be bid up to alter the ratio between savings and consumption until a new balance was found.

It also informs us of something else, and that is business is prepared to bid up for savings, instead of savings being merely a matter of savers deciding to defer a portion of their consumption. Consequently, central banks using interest rates to manipulate the savings rate is bound to fail, because it overrides rather than supplements the vital link between demand for capital, which emanates from business, and its supply from savers who would at the margin prefer to spend rather than save.

If it is great enough, the suppression of interest rates at some point will encourage businesses to invest more capital in production, but the motivation is no longer driven by expectations of future demand but by the opportunity for access to artificially cheapened borrowing. The propensity to save is materially reduced, fundamentally disrupting the market mechanism.

The reason for pointing all this out is that the empirical evidence also shows interest rates are ineffective as a tool of monetary policy for the purpose of controlling the general level of prices. But since the explanation eluded Keynes et. al. it was designated a paradox and simply ignored. Why did all the leading economists since Tooke who addressed the phenomenon miss the solution? In their ivory towers they had little or no experience or understanding of what it takes to be a successful businessman.

Nor, for that matter, have central bankers. Clearly, central bank policy with respect to interest rates is fatally flawed for this reason. That interest rates are not just the price of money but reflect the difference between possession of a good (not money!) and its future possession ties in the theory of exchange to Gibson’s paradox, not central bank assumptions that money is a separate good and interest is its price. It strikes at the heart of Keynesian economics and demolishes his understanding of how the boom and bust cycle should be managed.

In Chapter 22 of his General Theory, Keynes put forward his own explanation of the business cycle which briefly was as follows. He believed that fluctuations in the propensity to consume played a part. In other words, changes in the relationship between consumption and savings he described elsewhere as being governed by “animal spirits” and “the paradox of thrift”. But that’s a cop-out and not an explanation. Secondly, he believed that changes in liquidity preference were a factor, an argument that echoes his savings paradox but at a business level. Again, that is not an explanation, because it assumes money withheld from investment lies idle: it does not, unless it is held in cash notes, Instead, it is always being redeployed elsewhere through the banking system.

And thirdly, he cites the marginal efficiency of capital, an invention of his, which appears to describe the point at which the discounted value of an investment produces a return in excess of the rate of interest. This is also incorrect, the correct comparison being between alternative applications for the investment of capital. Furthermore, a businessman knows that in calculating the marginal efficiency of capital by discounting his investment over the life of a project is purely guesswork wrapped up in a mathematical model. He is better evaluating future markets for his product, where his knowledge and entrepreneurial instinct gives him an advantage, and then calculating the costs involved before deciding whether it is profitable for him.

None of this explains the cyclical nature of the business cycle. Here, Keynes gets into a muddle, claiming the bust is the result of organised investment markets under the influence of purchasers largely ignorant of what they are buying, and speculators chasing a quick buck instead of making a reasonable estimate of the future yield of capital assets. It is the condition, Keynes claimed, which leads to over-optimistic and over-bought markets that fall with sudden and catastrophic force.

Keynes clearly reckoned that as an economist he knew better than commercial businessmen their businesses clearing through markets, a view that persists with the neo-Keynesians planning monetary policy today, now developed even further into total control over markets.

Without adequate explanation Keynes then assumes “the dismay and uncertainty of the future” accompanies a collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital, followed by an increase in liquidity preference and hence a rise in interest rates. One would have thought the rise in interest rates was the prelude to the collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital and increasing liquidity preferences, rather than the way round Keynes assumes.

Much of the problem with Keynes’s economics are with his slippery definitions, many of which have now entered the economic lexicon. But this cursory examination of Chapter 22 on the business cycle in his General Theory reveals the principal errors that guide central bank policy makers to this day. Nowhere is there mentioned the role of bank credit expansion.

For a better understanding of the business cycle we turn to some basic pre-Keynesian theory.

What happens when there is no change in the money quantity

Before we can move on to what drives a boom and bust business cycle, we first must understand the condition of an economy with no change in the quantity of money. It matters not what the money is, only that it is accepted by everyone as money. That is to say, a commodity with the sole function of acting as an intermediary between the exchange of labour for goods and services and to facilitate the choice between different goods and different services. The root of exchange is not the money, but that it facilitates comparisons of value between goods.

It is therefore the basis behind the division of labour, famously described by French economist, Jean-Baptiste Say in 1803 in the following terms:

It is worthwhile to remark that a product is no sooner created than it, from that instant, affords a market for other products to the full extent of its own value. When the producer has put the finishing hand to his product he is most anxious to sell it immediately, lest its value should diminish in his hands nor is he less anxious to dispose of the money he may get for it; for the value of money is also perishable but the only way of getting rid of money is in the purchase of some product or other. Thus, the mere circumstance of creation of one product immediately opens a vent for other products.

And

Money performs but a momentary function in this double exchange and when the transaction is finally closed it will always be found that one kind of commodity has been exchanged for another. (A Treatise on Political Economy – 1803)

Bear in mind that this was written in uncertain times for France, following the collapse of assignats and mandats territoriaux, two forms of state-issued currency during the previous decade —hence the rejoinder about disposing of money immediately. Otherwise, it is a fair description of how producers and consumers, always different but the same people, use money and of its true purpose.

The import behind these two statements was subsequently given the title of Say’s law. They were so obviously true that Keynes had a problem getting around it so that an economic role could be created for the state, which was the hidden purpose behind his General Theory. His solution was to minimise any mention of Say’s law and to restrict it to one reference early on (page 26). And that reference was another of his slippery definitions:

“Thus Say’s law, that the aggregate demand price output as a whole is equal to its aggregate supply price for all volumes of output is equivalent to the proposition that there is no obstacle to full employment.”

This is not Say’s law. What is aggregate demand price output? It is pure nonsense as is aggregate supply price for all volumes of output. These high-sounding phrases deflect attention from the truisms in Say’s law, that we divide our labour to maximise our vendible output so that we can acquire the goods and services we need and desire. No mention is made of full employment. There will always be unemployment among those unable to work, the workshy, the sick and the elderly. But they need either their own savings to draw upon or benefactors to support them. Family, charities and the state perform this function, but in all these cases support must come from those that produce. Say’s law is not and never was equivalent to the proposition that there is no obstacle to full employment.

As to the unemployment question in the wider sense, neo-Keynesian manipulation of money and support for businesses that do not serve the consumer to his satisfaction have coincided with the rise of unemployment.

It will become obvious that the quantity of money in the economy is irrelevant for its efficient functioning, so to have a fixed amount of circulating currency will not impair the workings of the economy in any way. Goods and services are produced solely for the satisfaction of consumers and other businesses, all of which in turn also produce goods and services for others. The economy continually evolves, and through free markets scarce capital is deployed by entrepreneurs to be used as efficiently as possible for profits. The supply of capital comes from consumers’ savings together with money put aside for the purpose by producers themselves.

Consumers are encouraged by producers to defer some of their consumption by compensating them with an amount that exceeds the value they place on possession of current goods over possession at a future date. The mechanism, interest rates, are bid up to achieve the level of deferred consumption required to fund the necessary investment to produce the products demanded in the future. They will reflect three components: the originary rate, which can be equated to a general time preference reflecting the different values of possession and future possession; the risk of loss of capital; and an entrepreneurial value because bond holders and business owners share a common objective even though contractually their interests are separated.

The monetary capital made available to the entrepreneurial class is put together with other factors of production, such as labour, commodities, machinery, part-manufactures and an establishment to produce goods and services.

Thus, an economy has all that is needed to supply the evolving demands of consumers: a fixed quantity of money, part of which is retained in savings for investment in production, production and finally consumption itself. Businesses fail and others emerge. The division of labour ensures everyone is employed, with the exception of those unable to work, who are carried by others who are or supported by their savings.

Individual prices of goods and services rise and fall, according to changes in demand and the anticipation of producers to meet those changes. It is this environment where Schumpeter’s description of creative destruction applies. Production of goods and services that fail to produce expected returns are quickly abandoned and capital in all its forms redeployed to more productive and profitable uses. The arbiter in this process is always the consuming customer. Any business that fails to satisfy the customer fails itself.

In our example of a fixed money economy, government involvement merely redistributes existing money. Because a government is always bureaucratic and interventionist it detracts from the economic progress otherwise enjoyed, which is why a high spending government suppresses economic progress, while a low spending government permits a greater degree of economic progress. Non-monetary government intervention only changes the level of economic progress and does not lead to cyclical behaviour.

The effect of changes in the quantity of money

Now let us amend our model to accept fluctuations in the quantity of circulating money. We can now see that there is an additional factor to the conditions of Say’s law; there is money whose economic origin is not that of a selling producer or spending consumer. But being wholly fungible with existing money it does not have a different identity.

Without the state’s intervention, the source of extra money is bank credit. Banks create loan facilities, which in turn create deposits when loans are drawn down through payments made in the course of business. During a period of bank credit expansion, all banks will see increasing levels of deposits, and when these lead to imbalances for individual banks they are reconciled through wholesale money markets.

The expansion of bank credit favours the banks themselves and the bank’s lending customers, who get to benefit and spend it first before prices can reflect the additional currency in circulation. As the extra money is spent into increasingly wider distribution, it drives prices up behind it in what is known as the Cantillon effect. Eventually, it is fully absorbed into economic activities. But since production resources are relatively inelastic, the purchasing power of currency units declines as the greater quantity of money chases the same goods. This is reflected in an increase in the general level of prices.

But during the process of new money being absorbed into the economy, a cycle of economic activity develops. Initially, the extra money in circulation creates demand for goods and services that did not previously exist. A temporary boom in business activity takes place but only for those goods and services in the locations where the new money is spent. But unrecorded is the transfer of wealth that benefits early receivers of the new money, from those who only receive it later. The losers are obviously the savers whose capital buys less and the workers whose salaries are devalued.

The spread of rising prices affects businesses as well. As the extra money percolates through the economy they find that the cost of raw materials and commodities rises, driven by excess demand for them created by the additional money. Shortages of skilled labour develops, and the cost of labour rises. Waiting times for manufacturing equipment lengthens, and their prices rise as well. Other prices rise, such as establishment costs and the cost of energy. Meanwhile, the availability of monetary capital continues to expand as banks compete for business in the boom times.

At some point, the expansion of the banks’ balance sheets informs the prudent banker that even though times are good, some caution must prevail. The fall in the currency’s purchasing power has led to money being diverted from savings to consumption, because the time preference between possession and non-possession has increased. Even though higher levels of spending ensure money continues to circulate through the banks, they need to raise interest rates to maintain the balance between the extension of bank credit and the security of customer deposits. This is because there is an inherent risk for banks in funding term credit through checking accounts which can be drawn down without notice instead of term deposits.

The rise in interest rates disrupts producers’ business models and they begin to consider reallocating capital to other applications. As we have seen, in the case where there is a stable quantity of money, this is not a problem, essentially because changing business strategies in a fixed-money economy is a random process. Furthermore, the extension of production time that tends to accompany artificially supressed interest rates, illustrated by Hayek’s triangle, is never an issue in a fixed-money economy. But the effect of an expansion of money has been to ensure all businesses tend to act in the same way at the same time. A significant bias develops, so that the majority of businesses end up at a crossroads at the same time, reassessing businesses that have become unprofitable.

Commercial banks are sensitive to these changed conditions and are only too aware of the risks of extended lending to unprofitable businesses. At the same time therefore, bankers in the majority of banks arrive at the same conclusion, again all together: they should reduce lending risks for fear of being caught out in a slump.

The expansion of bank credit commences and gathers pace over an extended period of time, and then comes to a sudden halt. It is clear that the origin of the business cycle is found in an increase in the quantity of circulating money in the form of bank credit. Without changes in the quantity of bank credit, a cycle of business activity cannot develop.

The disruptive role of central banks

For some time, central banks have been extending their interventionist roles in an attempt to smooth the business cycle. Keynes and others wrote the textbooks for them, justifying the management of the banking sector through monetary policy, always ensuring the banks have enough liquidity on hand. They have extended their role from acting as lender of last resort to now flooding the economy with money even before it slumps, planning to “normalise” interest rates once confidence has returned.

We have seen that Gibson’s paradox negates this cornerstone of monetary policy. Figure 2 above illustrates the lack of correlation between the rate of inflation, which oscillates wildly while interest rates in free markets remained relatively stable.

Until price inflation took off in the 1970s, there was no correlation between wholesale borrowing rates and price inflation, not even in wartime. Yet, even though it has been shown that extreme interest rate suppression in the form of negative rates fails to affect price inflation — at least as measured by the consumer price index — central banks persist in supressing interest rates.

Instead of managing the cycle of bank credit, more recently central banks that had yet to do so have now resorted to outright monetary inflation, as nations attempt to defray the economic consequences of the Covid-19 panic. The Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank had even resorted to negative interest rates long before Covid-19, expanding their money quantities through quantitative easing continually to finance government spending. From June 2008, before the Lehman failure, the sum of the assets of the five major central banks (excluding China) totalled $4.4 trillion; they climbed to $21.8 trillion by the end of June. 10-year government bond yields range from 0.6% for the US to minus 0.47% for Germany and minus 0.51% for Switzerland. While it is not the place of any economist to second guess originary interest rates, these bond yields are clearly the result of their suppression through monetary inflation.

Then there is the seen and the unseen. We see the money handed out by the government to selected businesses and individuals funded by monetary inflation and deem it to be a good thing. What we do not see is the transfer of wealth that accompanies it from all citizens through monetary debasement. And as that debasement accelerates even further, it will only cease when there is no more wealth for the government and its central bank to acquire from the population by inflationary means.

Monetary expansion has now become unstoppable, because if it was to be stopped the accumulated economic distortions from as long ago as the Second World War — certainly in the case of nationalisations — would unwind. Unemployment would rise, demand collapse, and so prices would fall — a definite no-no for the Keynesians. Governments would lose their inflationary funding and would have to attract genuine savings, which in America and the UK in particular hardly exist today as a result of Keynesian policies. Interest rates would have to rise to normalise savings rates, but at the same time government demand for funding would deprive the productive economy of the monetary capital necessary for it to restructure itself.

There is now no policy alternative for democratically elected governments and their central banks to pursuing inflationary policies to their bitter end. They have failed to extend the boom so that the slump can be avoided. They do not understand that the boom bust cycle is a phenomenon of bank credit expansion, instead making the error of believing in Keynes’s animal spirits — reiterated by Alan Greenspan twenty years ago as irrational exuberance.

No one has a mandate to rein it in. Ultimately, the ever-increasing pace of monetary expansion required to postpone the bust will destroy the currencies of all nations following neo-Keynesian monetary policies. And with the currencies will go all the personal wealth through the mechanism of inflationary transfer.

Covid-19 is only bringing forward a certain end to the abject failure and the hubris behind neo-Keynesian nonsense.

By Alasdair Macleod, www.goldmoney.com

Find more: Contributing Authors