Asian Stocks Extend Weekly Drop With Oil Below $45; Lira Weakens

-

Manager’s team said to order unwanted cards for Wachovia staff

-

Leaders ‘intently focused’ on restoring trust after CEO’s exit

After Wells Fargo & Co. executive John Sotoodeh handed off more than a hundred branches in Southern California to a colleague in 2009, problems surfaced quickly.

His successor, Kim Young, addressing rumors that some employees were opening bogus accounts, called an introductory meeting with staff and warned she wouldn’t tolerate misconduct. Within a few days, managers recall, sales crumbled across her new turf.

Sotoodeh, who started as a teller in 1990, has since climbed even higher. He’s now one of three regional chiefs running the firm’s nationwide consumer-banking empire. Young spent the final years of her four-decade career at Wells Fargo weeding out bad employees, retiring in 2014.

In interviews, more than a dozen past and current Wells Fargo employees — many of them senior managers — chronicled how a generation of executives thrived in its ambitious sales culture, winning accolades and promotions, while being held aloft as examples to colleagues. All the while, people under them were opening legions of unwanted accounts for customers.

As Wells Fargo grew, some stars fanned out from Southern California, described by colleagues and in congressional testimony as a focal point of the rampant misconduct, spreading a culture that lionized boosting sales.

Firings Pending

Wells Fargo declined to make managers available for interviews but said in a statement that its leaders are closely examining the abuses and are “intently focused” on restoring customers’ trust. Many of those mentioned in this story, including Sotoodeh, referred questions to company spokesmen. Others declined to comment or didn’t respond to messages.

Company executives already have identified some current managers to be fired, according to a person with knowledge of an internal investigation. The terminations are being delayed so employees can aid inquiries, said the person, who asked not to be named discussing the matter. The person declined to specify who may be poised to lose their jobs.

No one interviewed said they heard senior executives instruct underlings to open bogus accounts, though more than a half-dozen bankers said low-level managers privately coached them to do so. More often, employees said, managers taught underlings to use misleading sales pitches — such as telling customers a checking account came with a credit card — or they balked when subordinates raised concerns. At the least, former managers say, many executives failed to stamp out misconduct for years despite ample signs it was flourishing below them as their own careers advanced.

“No one was ever penalized for doing the wrong thing until there was critical mass,” said Michael Bruns, a banker at Wells Fargo branches in Silicon Valley from 2009 to 2012. “Instead, they were promoted. They became our bosses and the people who are running the company today.”

Bruns said he was fired two months after complaining to the bank’s ethics hotline about his colleagues’ sales practices.

Broad Review

In the statement, Wells Fargo said it takes allegations such as Bruns’s seriously and will examine them thoroughly. The San Francisco-based bank has policies prohibiting retaliation for reporting suspected misconduct, and it’s conducting an “an end-to-end review” of the hotline process. The company said Thursday in a quarterly regulatory filing that the Securities and Exchange Commission is among the authorities examiningits sales practices.

More broadly, the lender said it’s taking a hard look at what happened.

“The company’s leadership is intently focused on restoring trust in its community bank, making things right with customers and taking actions intended to ensure sales-practices issues do not happen again,” Wells Fargo said. “Actions have included naming a new head of retail banking, eliminating product-sales goals and changing the retail bank’s risk-management processes and protocols for customer-account activity. As we have disclosed, there are multiple investigations under way to address sales-practice issues, including by an independent committee of the board of directors. The integrity of these investigations is not served by commenting on speculation and rumor. The company will take accountability actions, as appropriate, once it has the facts necessary to act.”

The scandal exploded in September with the announcement of $185 million in fines, prompting John Stumpf to step down weeks later as chairman and chief executive officer. Carrie Tolstedt, who oversaw the consumer unit from 2006 until July this year, also left. Together, they’re giving up about $60 million of unvested stock. Neither responded to messages seeking comment.

The bank’s board has publicly promised to investigate how fake accounts proliferated, potentially punishing more executives as warranted.

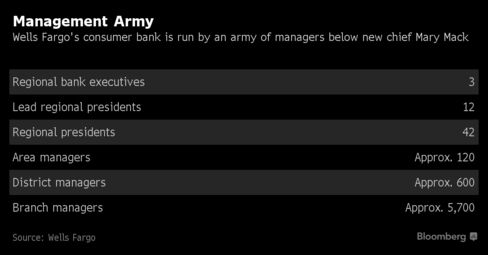

That’s a monumental task: The firm’s most recent annual report shows the community bank’s three U.S. regional chiefs oversee more than 50 regional presidents. Below them, there are about 120 area presidents, each with their own cluster of branches.

The bank terminated only one member of that army — an area president — for improper sales over half a decade while firing more than 5,000 lower-level workers, Stumpf said while testifying to a U.S. Senate panel in September.

One question lawmakers want answered is whether any of those who remain ever directed employees to open accounts without customers’ permission or ignored such misconduct, which authorities have said was widespread. The board’s review is expected to take months, according to a person with knowledge of the process. A board spokesman declined to comment.

“We failed to acknowledge the role leadership played and, as a result, many felt we blamed our team members,” Stumpf’s successor as CEO, Tim Sloan, said in a speech to staff on Oct. 25. “That one still hurts, and I am committed to rectifying it.”

At the heart of Wells Fargo’s sales culture was a metric developed by top brass more than a decade ago, tracking how many financial products and accounts — now dubbed “solutions” — branch employees sold daily. Back then, the focus appeared to be different.

Les Biller, chief operating officer from 1998 to 2002, mainly used the figure to set staffing levels, one former senior manager said. If employees fielded more than a certain number of solutions daily, it might signal more tellers were needed at an overworked branch. Biller didn’t respond to messages seeking comment.

‘Motivator Report’

Under Tolstedt, 56, sales volume was the ultimate measure of performance, former employees said. Managers urged workers to boost daily sales and persuade each customer to sign up for more Wells Fargo products, a practice known as cross-selling.

Tolstedt ran the division with a style that former colleagues describe as intense and driven, and unrelentingly focused on numbers showing growth. Branch personnel were assigned sales targets that, for years, kept climbing. Their progress was tracked in what some called a “Motivator Report,” which circulated daily to managers. It set the tone for conference calls, in which supervisors pressed people below them to meet quotas.

Stumpf brought them up, too, e-mailing high-performing managers to congratulate them and often citing their figures when stopping by local offices, according to one former manager.

The bank has said it took steps to prevent cheating, such as increasing ethics training and lowering targets to win bonuses. One manager credited Tolstedt for introducing more metrics to track customer service and satisfaction, emphasizing a need for quality.

But for many, the focus on hitting or beating quotas was a monster that underperformers dreaded and the ambitious tried to lasso. Managers who boosted sales typically rose fastest, and some talked incessantly about strategies for doing that, the employees said.

Stories of Southern California bankers opening 42 debit cards in a single day percolated among astonished managers in other areas, one person recalled. Several managers who tried to gauge their progress relative to peers said California and Florida often stood out for their new accounts, though many of them were hardly used.

After some managers alerted their bosses that the numbers seemed suspicious, they said they were told to mind their own results. Some said they then watched their supervisors climb higher, or at least continued to hold senior posts within the division.

Wells Fargo’s three U.S. consumer-banking chiefs report to Tolstedt’s successor, Mary Mack.

Two of them built their careers in California: Lisa Stevens, 46, was promoted to run the state in 2009, and later expanded her territory to cover the Pacific Midwest region, which arcs eastward toward Ohio. She also heads small-business banking. Sotoodeh, 46, oversaw Los Angeles and Orange County before his promotion to lead other Southwest states from Texas.

The third region, the East Coast, was run by another former California chief, Laura Schulte, from 2009 until her retirement in 2014. Tolstedt moved her to Charlotte, North Carolina, just after Wells Fargo bought Wachovia Corp., giving her a key role in integrating the companies. Schulte said in an e-mail to Bloomberg that executives picked her “due to my extensive experience as a transition manager over several years and acquisitions, rather than anything related to sales practices.”

All-Stars

Still, she’s remembered by some staff for an internal sales promotion called “Schulte’s All Stars.” A 2010 copy of the list obtained by Bloomberg ranks managers by a mix of metrics, all gauging volume in different ways. Some were on track to be in the “Schulte Hall of Fame.”

Such lists were “scrubbed carefully so that any one of my winners did not include anyone who was known to be under scrutiny for sales practices,” Schulte said in her e-mail. She said she wasn’t focused primarily on sales numbers, and that she also ran “recognition events” tied to employee satisfaction, turnover, customer service and other measures of quality. Promotions, too, were based on a variety of criteria, she said.

Schulte also brought along a pair of California all-stars. Darryl Harmon became head of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee, and Shelley Freeman ran Florida.

Freeman, who previously oversaw metropolitan Los Angeles, soon tried to duplicate its sales-centric culture, former employees said. Every Monday, she wrote an e-mail to thousands of Florida personnel to encourage them to sell, sometimes describing the kind of lifestyle they might hope to achieve. She mentioned her Super Bowl tickets and buying an $800 pair of sunglasses at the beach, one former manager recalled. The messages went to tellers making $12 an hour.

Freeman now heads the bank’s consumer credit-card business. She said she couldn’t immediately comment when reached by phone, and later didn’t respond to messages.

Forty-five people who worked in Wells Fargo’s Florida branches have stepped forward to join a wrongful termination and retaliation lawsuit filed in September by Los Angeles employment lawyer Jonathan Delshad. It was the first such case to be brought after the fines. He provided Bloomberg with a state-by-state breakdown of the roughly 500 potential plaintiffs vetted by his firm so far, showing only California has more, with 144.

The complaint, filed in Los Angeles Superior Court, seeks class-action status for employees ousted or demoted for missing sales quotas while refusing to cheat customers.

Training Sessions

Some of Sotoodeh’s team also got involved with new branches in the Southeast. In 2010, members of his staff went to train Wachovia bankers working under Harmon. Soon after the coaches left, the Wachovia staff discovered debit cards in their mailboxes for Wells Fargo accounts they hadn’t requested, one person said. The bankers learned months later that members of Sotoodeh’s team had used local customers’ identities to help meet sales goals, the person said.

Wells Fargo’s internal crackdown intensified in the years after Sotoodeh handed Young the swath of branches stretching from San Bernardino County to San Diego.

In 2011, the bank created a “report card” to help track sales practices in California, and it delegated a team to sift data for patterns suggesting accounts were bogus, Stumpf told the Senate panel. Two years later, that group launched an “intensive investigation” in Los Angeles and neighboring Orange County into a practice known as “simulated funding,” he said. At the time, Sotoodeh oversaw both areas.

Employees were opening bogus accounts, then depositing funds temporarily to make it look like customers were using them, Stumpf testified. He conceded to lawmakers that sales abuses were especially prevalent in Southern California, and not just because the bank’s presence there was large. Both the report card and funding review later expanded nationwide.

Climbing Ranks

Other managers from California also assumed leadership posts overseeing broader U.S. regions. Pam Conboy supervised the San Gabriel Valley to the east of Los Angeles when Tolstedt was picked to run the state in 2000. Tolstedt promoted Conboy within the state, and later flew her around the country to teach strategies for increasing sales, managers say. She now oversees Arizona, Nevada and Utah. Conboy didn’t respond to messages seeking comment.

Conboy, Sotoodeh and Stevens have outlasted many of their colleagues. Of the almost 70 regional supervisors listed in the company’s 1999 annual report, they’re among fewer than 10 whose names still appeared in an updated hierarchy posted this year.

A number of other managers who came up under Sotoodeh around Los Angeles and Orange County are now regional presidents overseeing parts of California and Texas. David DiCristofaro runs greater Los Angeles. Ben Alvarado runs the region that Sotoodeh once handed to Young. Reza Razzaghipour manages an area stretching from Ventura and Santa Barbara inland to Tulare County, while his spouse, Marla Clemow, presides over metropolitan Los Angeles. They declined to comment or didn’t respond to messages.

One of their peers, Darryl Montgomery, leads Houston. He was the most senior manager below Tolstedt named in a lawsuit by ex-Wells Fargo employees claiming they were unfairly pressed to meet sales quotas, according to a Bloomberg review of more than 40 court cases. While that 2014 complaint against Wells Fargo is continuing in Los Angeles Superior Court, claims against Montgomery were extinguished in July. He didn’t respond to phone messages.

Overhauling Incentives

Wells Fargo has said it scaled back, and ultimately eliminated, sales goals that regulators faulted for encouraging abusive cross-selling. A new performance plan for retail bankers will be introduced next year. It’ll be based on customer service, growth and risk management.

The company created a human resources team to help rehire employees who left for performance reasons, Sloan told staff in his speech. And it will hire consultants to review sales practices and address “cultural weaknesses that need to be strengthened or fixed,” he said.

“I think it all begins with understanding where things broke down, and where we failed — as a culture, a company and as leaders,” he said.

Still, there’s “a risk of over-correcting” the bank’s sales practices, Sloan told investors Thursday at an investors’ conference in Boston. “There’s nothing wrong with cross-sell done right,” he said, adding that its businesses outside of the retail bank are performing well.

Six years ago, former Wachovia banker Joe Coyne helped run some of Schulte’s programs on the East Coast to drive up numbers, such as one called “Jump Into 2010.” To many managers back then, his was a voice of encouragement, singling out those who beat targets and spurring them to do more.

“The performance you both planned for and delivered is nothing short of incredible,” he wrote in a staff update on the 2010 campaign. “You have raised the bar higher than many thought possible.” He referred questions about that work to the bank’s spokesmen.

Last year, Wells Fargo promoted him to a key post within its risk office. Coyne now oversees sales practices across the company’s divisions, looking for any conduct that might cause problems.

Source: Bloomberg