The Four D’s that define the future

When the money runs out or loses its purchasing power, all sorts of complexity that were previously viewed as essential crumble to dust.

Four D’s will define 2020-2025: derealization, denormalization, decomplexification and decoherence. That’s a lot of D’s. Let’s take them one at a time.

I use the word derealization to describe the inner disconnect between what we experience and what the propaganda / marketing complex we live in tells us we should be experiencing.

Put another way: our lived experience is derealized (dismissed as not real) by official spin and propaganda.

The current state of the economy is a good example. We see the real-world economy declining yet the officially approved narrative is that there’s a V-shaped recovery underway because Big Tech stocks are hitting new highs. In other words, we don’t need a real-world economy, all we need is a digital economy provided by Big Tech platforms.

This is derealization at its finest: the everyday world you experience directly no longer matters; what matters is stock prices and various statistics that all paint a rosy picture.

Meanwhile, the wealthiest class is fleeing soon-to-be-bankrupt cities. The wealthiest class has the means to buy the best advice and also has the most to lose, so I give their actions far more credence than official propaganda.

I’ve sketched out my thesis on denormalization in The “New Normal” Is De-Normalization and Here’s Why the “Impossible” Economic Collapse Is Unavoidable:

This is why denormalization is an extinction event for much of our high-cost, high-complexity, heavily regulated economy. Subsidizing high costs doesn’t stop the dominoes from falling, as subsidies are not a substitute for the virtuous cycle of re-investment.

The Fed’s project of lowering the cost of capital to zero doesn’t generate this virtuous cycle; all it does is encourage socially useless speculative predation. Collapse isn’t “impossible,” it’s unavoidable.

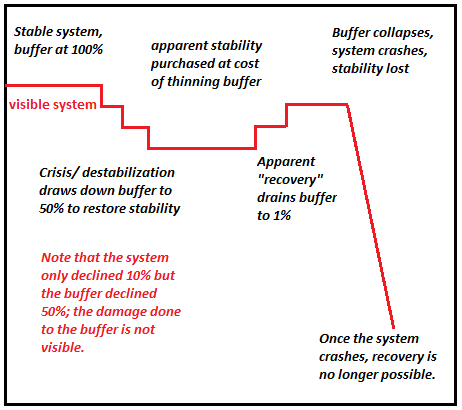

The basic idea is that all the structures of the “normal” economy only function at full capacity, as costs have moved higher, unproductive complexity has increased and our ability to pay these higher costs is based on ever-expanding debt.

As a result, “normal” became extremely fragile and binary: it’s either fully funded at full capacity or it collapses. The structures of everyday life (to use Braudel’s apt phrase) are incapable of downsizing to 70% of their previous complexity and cost, much less 50%.

There won’t be any “new normal” because the system has become too rigid, ossified, over-regulated and controlled by entrenched interests and elites. It is incapable of reducing complexity and cost, and bailouts via borrowed money are stopgaps, not actual solutions.

Decomplexification is a mouthful, and everyone inside the machine knows the impossibility of paring organizational complexity. Everyone who is a stakeholder in the status quo (which is virtually every employee, manager, etc.) will fight to keep the status quo intact as is, for fear that any re-organization might imperil their livelihood or security. This is entirely understandable, of course.

Modern life is inherently complex. Democracy is complex and cumbersome because having a bunch of stakeholders all competing for public resources and advocating for a bigger slice of the pie is inherently messy. There must be oversight and feedback to minimize the possibility of one clique gaining complete power.

Long global supply chains are inherently complex. Managing ever-increasing regulations is inherently complex. And so on.

When the money runs out or loses its purchasing power, all sorts of complexity that were previously viewed as essential crumble to dust. We’re witnessing the early stages of this in real time in healthcare and education: overly complex and costly systems are breaking down not just from the challenges of the pandemic but because they’re structurally incapable of adapting or evolving beyond pseudo-reforms and policy tweaks.

As an illustration, consider the current overly complex way our healthcare system funds itself and a system in which customers pay cash for medical care: no insurance, minimal oversight auditing, etc. Regulations boil down to a requirement to publicly post prices for services and actually charge only the posted prices.

In higher education, as per the model I outline in my book The Nearly Free University, the campus and its entire bureaucracy becomes superfluous. Classes, embedded apprenticeships and in-person workshops are organized online. The entire scheme of accrediting colleges is jettisoned in favor of accrediting each student.

And so on. You can see the problem: eliminating unproductive, obsolete layers of costly complexity will eliminate millions of middle-class jobs that can’t be replaced with new expansive bureaucracies.

Yes, paying cash for healthcare and campus-less, mostly automated universities are oversimplifications. So where is the middle ground between current costly complexity and some “new normal” with half the costs and complexity? There’s no way to accomplish this while retaining the payrolls, priorities, processes and structures of the existing systems.

The point here is that when the money runs out or loses much of its purchasing power, overly costly complexity collapses whether we like it or not.

Decoherence is an interesting word. In science, “Decoherence can be viewed as the loss of information from a system into the environment, since every system is loosely coupled with the energetic state of its surroundings.”

Decoherence refers to the loss of systemic coherence between narratives, values, processes and systems. Simply put, stuff no longer works right and it no longer makes sense.

What worked in the past has been transformed by two systemic drifts:

1. Systems that evolved to function in a specific socio-political-economic context continued adding complexity and cost because debt-based funding was available, not because they were becoming more efficient or effective.

2. The socio-political-economic context has changed and so the status quo systems are mal-adapted, i.e. obsolete.

These two systemic drifts occur so slowly that we aren’t even aware of the loss of coherence unless we compare the current system to a previous set point or look at it from the perspective of starting from scratch: what would the most sustainable, lowest-energy consumption, most efficient and productive system look like if we designed it from scratch? It certainly wouldn’t be the system we have now,

The four Ds help us understand why the status quo is incapable of adapting / evolving fast enough and effectively enough to manage a controlled collapse to a much lower level of cost and complexity.

The status quo can’t even admit the need for a controlled collapse, much less manage it.

We can add a fifth D: denial. The four Ds are already in motion and denial is only accelerating systemic decoherence.

By Charles Hugh Smith, www.charleshughsmith.blogspot.com

Find more: Contributing Authors