The monetary logic for gold and silver

A considered reflection of current events leads to only one conclusion, and that is accelerating inflation of the dollar’s money supply is firmly on the path to destroying the dollar’s purchasing power — completely.

This article looks at the theoretical and empirical evidence from previous fiat money collapses in order to impart the knowledge necessary for individuals to seek early protection from an annihilation of fiat currencies. It assesses the likely speed of the collapse of fiat money and debates the future of money in a post-fiat world, in which the likely successors are metallic money — gold and silver— and some would say cryptocurrencies.

Early action to lessen the impact of a failure of the fiat regime requires an understanding of the role of money in order to decide what will be the future money when fiat dies. Will we be pricing goods and services in gold or a cryptocurrency? Will gold be priced in bitcoin or bitcoin priced in gold? And if bitcoin is priced in gold, will its function of a store of value still exist?

Introduction

This week saw the news that a vaccine had been found to combat the coronavirus. At least it offers the prospect of humanity ridding itself of the virus in due course, but it will not be enough to rescue the global economy from its deeper problems. Monetary inflation is therefore far from running its course.

The reaction in financial markets to the vaccine news was contradictory: equity markets rallied strongly ignoring rapidly deteriorating fundamentals, and gold slumped on a minor recovery in the dollar’s trade weighted index. Rather than blindly accepting the reasons for outcomes put forward by the financial press we must accept that during these inflationary times that markets are not functioning efficiently.

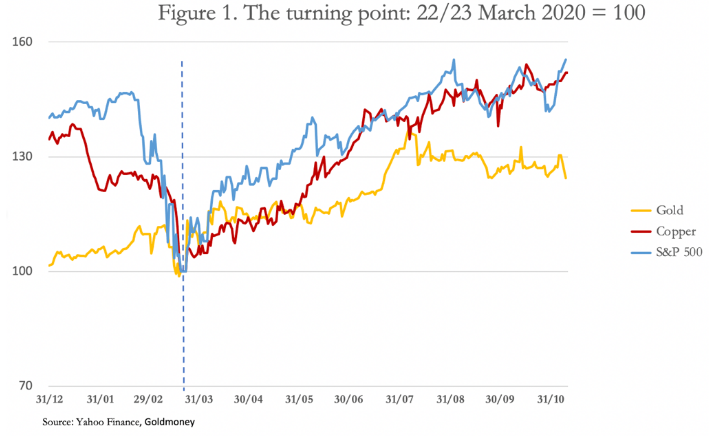

To obtain a grasp of what is truly happening in capital markets, it is usually best to stand back and observe the broader context. Figure 1 below shows the course of three major indicators this year: the S&P 500 index as proxy for the stock market, the copper price as proxy for industrial commodities and gold as proxy for monetary inflation.

Before 22 March, the stock market had slumped along with copper, and gold had broadly flat-lined. The signals suggested that stock markets and commodity prices were discounting an economic slump, and that gold perhaps offered a haven from systemic risk, at least until it fell sharply in late March.

On Thursday, 16 March, the Federal Reserve Board cut its funds rate to zero and the following Monday, 23 March, the Fed declared unlimited quantitative easing to support the economy through what it declared would be a V-shaped recovery. In other words, an injection of money was expected to ensure economic recovery and a return to normality. March was also the month many countries entered lockdowns to combat the first wave of viral infections.

Following the Fed’s announcement, stock markets recovered sharply, being the direct beneficiaries of unlimited monetary expansion, which we discuss later. Copper recovered strongly, it was said to be on improved prospects for the global economy, but the back story here is more concerning. Following the Fed’s statement, China’s government decided to reduce its stockpile of dollars by buying key industrial commodities, particularly copper. If widely adopted by other foreigners and subsequently the American public, it is a policy that will ultimately destroy the dollar’s purchasing power.

The threat of infinite money printing to the purchasing power of the dollar drove the gold price to new highs, but it can be seen in Figure 1 that gold generally underperformed equities and copper by a significant margin. In one sentence, the reason is the establishment’s dislike and suppression of gold as a rival to fiat currencies, and ignorance in the financial community about the effects and consequences of monetary inflation.

This article is intended to put the latter right and to give the reader an advantage of knowledge in a subject which is bound to dominate financial markets and their underlying economies in the months to come.

The evolution of money and what it represents

In the pre-dawn of history, when the limitations of barter became an impediment to further human progress, two conditions needed to be satisfied. A form of intermediary good commonly accepted as a medium of exchange was indispensable so that through the division of labour and by their individual skills and knowledge, humans could maximise their output in order to acquire other goods to satisfy their needs and wants. The classical economists defined the division of labour and with it the role of money as Say’s law, after the French economist, Jean-Baptise Say (1767—1832), who described it.

The economic benefits of the division of labour are now taken for granted, even by socialists who are otherwise scathing of free markets. And the intermediary good, money, evolved to become commonly accepted by diverse communities, even those which did not trade with each other. Eventually, all civilisations accepted metallic money as the durable, reliable and quantifiable units of exchange.

In descending order of value, that which we would term their purchasing power today, metallic monies were gold, silver and copper. Before the dawn of history, when scribes began to document events, metallic money had already become established. History then recorded numerous occasions when the powerful deceived the public by corrupting money — obtaining it for themselves while forcing the public to accept inferior or worthless substitutes.

The Emperor Nero famously debased the Roman denarius to pay his troops, an act necessary for his personal survival, and a policy pursued by his successors for two centuries. In China, Kublai Khan confiscated gold, silver and precious stones, doling out paper substitutes made from mulberry leaves. From ancient times to the present day, kings, emperors and now governments more often than not were and still are heavily indebted and authorised schemes to replace gold and silver with debased coinage, or their own alternative forms of money. The public’s choice of a medium of exchange was incorruptible; a ruler’s choice was made with the intention to debase it as a source of finance.

Gold and silver had long been accepted as the medium of exchange, chosen by those that use it. The fact that its quantity could not be expanded by a government was no impediment to the advancement of national and personal wealth. The improvement of living standards throughout Europe and America in the nineteenth century was testament to the combination of free markets and sound money.

The limitations imposed by metallic money on the state’s ambitions were seen as a hindrance by socialising governments. The modern template for a resolution of the problem was the Prussian-led federation of German states, unified in 1871 by Otto von Bismarck. Accordingly, when Georg Knapp promoted his state theory of money in 1905, Bismarck furthered his statist ambitions by seizing the opportunity given by Knapp’s state theory of money to finance the expansion of Germany’s military forces, issuing marks unbacked by gold while still on a gold standard.

In August 1914 Germany’s gold exchange standard was temporarily abandoned, and when it became clear that the war was not going to be the short conflict which Germany expected to win, the purchasing power of the paper mark began to fall, collapsing to a notional trillion paper marks to one gold mark in November 1923. Other European currencies without a gold exchange standard and who put vast quantities of unbacked money into circulation also suffered monetary collapses, notably those of Austria, Hungary, Poland and Russia.

Bismarck showed in the years before the First World War that the gold standard was not necessarily protection against monetary debasement. Similarly, Benjamin Strong, the Chairman of America’s Federal Reserve Board, in the early 1920s used inflationary monetary policies under cover of the gold standard, and with the cyclical expansion of bank credit fuelled an unsustainable boom in the 1920s. The result was a stock market collapse, a banking crisis, the ownership of gold banned for American residents in 1933 and a substantial devaluation of the dollar against gold in January 1934. Gold then remained exchangeable for dollars, but only for the settlement of overseas trade.

From these changes, the current monetary situation evolved, driven by a new breed of economist which abandoned classical economics. Classical economics had emphasised the importance of free markets and the immutability of Say’s law. Instead, the mass unemployment in the 1930s was taken as evidence that free markets and the division of labour had failed, and that the state had an interventionist role to ensure that a depression would never happen again.

Despite all the evidence and a priori theory that explains the massive improvements in the human condition that arose from the division of labour and free markets, the denial of Say’s law was formalised by Keynes in his General Theory. Or rather, he skated around the subject, concluding that, “If, however, this is not the true law relating the aggregate demand and supply functions, there is a vitally important chapter of economic theory which remains to be written and without which all discussions concerning the volume of aggregate employment are futile.” Note that Keynes does not deny Say’s law as his acolytes do; he merely supposes that “If it is not the true law”.

From Keynes’s supposition he went on to invent macroeconomics, a mathematically based discipline that substituted human action with aggregates and averages. It justified the temporary budget deficits that are intended to stimulate a slumping economy by monetary inflation — deficits that have now become permanent and increasingly beyond control. By inventing an economic role for the state, Keynes opened the door to unlimited statist intervention and for the generally non-productive state to become an increasing burden on the productive private sector.

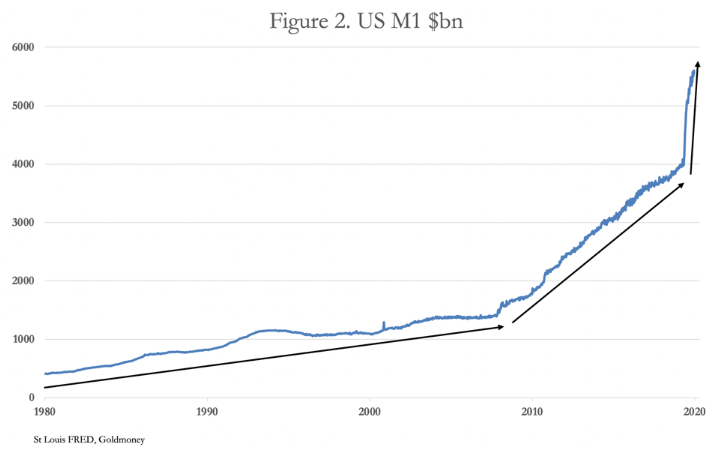

With the raison d’être provided by macroeconomics and questionable government statistics, the reliance by governments on inflationary financing has increased over time. We are now at the point when some observers of monetary history warn of hyperinflation. Figure 2 shows the course of the narrow money expansion of dollars in recent years.

The annualised rate of increase of the quantity of narrow money has grown in three phases since the end of the 1970s decade of price inflation. Since last January, it has risen to over 50%; not being more than that is only due to further planned inflationary stimulus being delayed by the presidential election. But in the second half of the fiscal year to last September, inflationary financing of the government’s budget deficit exceeded tax revenues for the first time.

With this evidence a neutral observer is certain to conclude that monetary debasement of the dollar appears to be out of control. And having replaced gold as the world’s reserve currency, the consequences for all fiat currencies and the global economy of the dollar’s looming failure are no less than disastrous. It is hardly surprising that alternative forms of money with restricted increases in circulation are rising in dollar prices. These include the peoples’ metallic monies, gold and silver, to which we can add a new phenomenon, cryptocurrencies and especially its flagship — bitcoin.

Having set the scene in the broadest sense, the next task is to explain why there is no escape from further monetary debasement, which might clarify why markets now appear to be discounting it in rising prices for gold, silver, wider commodities such as copper, and also bitcoin.

The outcome of monetary debasement

It is a common misconception among monetarists that the relationship between the quantity of money and its purchasing power is the only determinant of the relationship. There are two other important factors involved: the fact that additional money takes time to be absorbed into circulation with consequences; and its purchasing power is also determined by changes in the public’s general preference for holding money relative to goods.

The temporal shift in the first factor has important effects, in particular transferring wealth from late receivers to early receivers of the additional currency in the Cantillon effect. And when a government agency, such as its central bank, is the issuer, the ultimate beneficiary is the state at the expense of its people, with important consequences for future inflationary issues.

The importance of the second factor can be illustrated by what happens when the general public realises that all hope of a recovery in money’s purchasing power must be abandoned. Irrespective of the quantity in circulation, the public’s final rejection of an unbacked state currency will render it useless as a medium of exchange. That is the eventual outcome of the unfettered inflation of the money supply. And there are important characteristics to note on the path to that outcome.

As the quantity of money is increased and its purchasing power declines, the desire for cash and the maintenance of bank deposit balances inevitably declines as well. Initially, the evidence is found in rising prices for assets, both financial and real, and explains why, despite deteriorating economic conditions, equity prices and other assets which are not future claims on fixed quantities of money are rising, measured in depreciating currencies.

Until late-2019 these effects were hidden from view by three further influences, two active and one passive. Firstly, large amounts of dollar deposits were absorbed in a carry trade through the fx swap market, whereby hedge funds borrowed euros and Japanese yen to buy dollars, thereby benefiting from an interest rate arbitrage. This led to a large quantity of dollar bank deposits being tied up by speculators directly or indirectly, preventing their disposal for other financial assets (except through the mechanism of bank credit expansion) and therefore retarding the disposal of the total quantity of deposit dollars for commodities and goods. It was the popularity of this trade which ate up the balance sheet capacity of the largest banks, the global systemically important banks — G-SIBs, leading to a banking liquidity crisis that surfaced in the repo market in September 2019.

The second offset to deposit mobility occurred when the Fed reduced its funds rate, removing the reason for the interest rate arbitrage. The dollars freed by that move were partially absorbed by the contraction of bank credit. When interest rates are reduced so that a lender then realises that he has insufficient interest compensation to offset against the future value of the loan, he will decline to make the loan. The refusal can be blamed either on an increase in the level of loan risk in the prevailing economic conditions, or the lender’s realisation that the purchasing power of money is bound to decline over time leading to certain loss. Inflationist economists call the situation deflationary because it works against their desired policies.

The third and passive factor is the large quantity of dollar securities and bank deposits already accumulated by foreigners. Not only did that accumulation delay the price effects of monetary expansion through import substitution, but the deposit element of about $6 trillion ended up being in firm hands.

Now that the global economy has entered a slump, the stock of foreign owned dollar-denominated securities and dollar cash is likely to be reduced, because the dollar is over-owned by foreigners for the evolving trading conditions. As noted above, the Chinese have already decided to reduce their preference for dollars and US Treasury bonds in favour of stockpiling commodities — the very behaviour that more widely leads to a final rush out of a fiat currency into goods not immediately needed. According to the US Treasury’s TIC figures, foreigners own an estimated $20.5 trillion in financial securities and a further $6.3 trillion in short-term bills and bank deposits. If other foreigners follow the Chinese in reducing their dollar investments and deposits, it could be catastrophic for the dollar on the foreign exchanges and its purchasing power in the commodity markets.

The evolving crisis of dollar balances held by domestic users

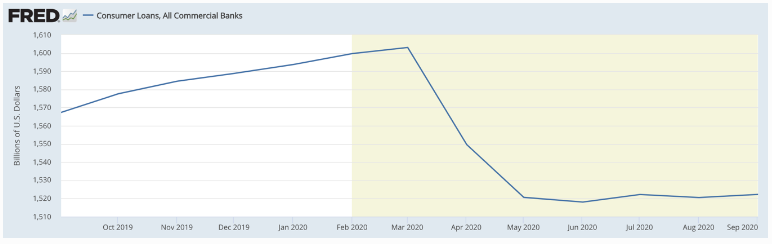

With the covid lockdowns and the damage being done to the economy, bankers are probably focused more on the elements of risk in an economic crisis than the money’s future purchasing power. But at a time when central banks like the Fed are churning out increasing quantities of money, the public’s use of it has not kept pace with the increased quantity. This is partially illustrated by the contraction of consumer loans that coincided with the helicopter drop of money by the government; in other words, instead of adding to their deposits by borrowing, consumers took the opportunity to reduce some of their debts to lower their cash and credit balances, as illustrated in the graph below.[i]

The effects of hedge fund speculation and the contraction of bank credit have concealed the general public’s reduced preference for money relative to goods. The public is dumping money to acquire all financial assets which are not fixed claims on debt. Irrespective of the fundamental factors faced by corporations, their share prices continue to rise, principally driven by a reluctance to hold money. With the exception of a seller’s proceeds being absorbed by the contraction of bank credit, the proceeds of an asset sale end up being reinvested in other financial assets.

Consumer liquidity has therefore become a matter of pass-the-parcel, with the public progressively less keen to hold money. It is now a short step for the public to anticipate the effects on a wider range of prices of further monetary debasement, and from there to realise that money is losing its purchasing power not just relative to financial assets, but to commodities and goods as well.

It is against this background of changing public perceptions about the value of retaining cash balances that the Fed continues to inject more currency into the economy. The new government, whoever becomes President, intends for part of the stimulus to be a further helicopter drop. As we saw with the first case, that cash is bound to be either used to chase goods not being produced in quantities to match the new money, or to pay down indebtedness. The flood of new money into hands which are reducing their cash balances is bound to accelerate the dollar’s loss of purchasing power.

Further consequences of the dollar’s debasement

If the process of monetary debasement leads to further rejections of cash and deposit money, it will become increasingly reflected in the dollar’s loss of purchasing power measured in prices of everyday goods, so much so that the result will become greater than the additional quantities of the dollar suggests is warranted. It was this effect that led to a shortage of notes in cash-based economies which have suffered an inflationary destruction of money, prompting the issuing authorities to accelerate their note production. The contemporary position is different.

The US and other westernised economies have reduced the use of cash, many with the intention of banishing it altogether. Consumers today use debit and credit cards, which remove the necessity of obtaining physical cash notes to spend, and therefore the disposal of deposit balances in an inflation crisis is instantaneous.

But this does not immediately discourage the monetary authorities from attempting to stimulate consumer spending. As we have seen, money has been fed directly into consumers’ bank accounts, and once the presidential election hiatus in America is resolved, it is anticipated that there will be a further helicopter money drop. With the economy tanking, the neo-Keynesians remain wedded to the idea that the economy lacks sufficient demand. For them there can be no turning back from inflationary policies, and the destruction of the dollar’s purchasing power then becomes a certainty.

As noted above, the debasement of a currency transfers wealth from producers and consumers to the government. It is a process that impoverishes the private sector instead of stimulating it into some vision of wealthless recovery. Not only does the naivety of neo-Keynesian macroeconomists guarantee there will be no let-up in the pace of monetary inflation, but the progressive impoverishment of ordinary people will require a further acceleration of the inflation process for a given transfer of real wealth.

The suppression of interest rates seals this Faustian deal by discouraging lenders from providing loans at rates that fail to compensate them for the future value of their capital, a problem that is only compounded by increasing perceptions of counterparty risk. With its policy of negative interest rates, the European Central Bank has succeeded in turning the whole Eurozone into an economic zombie. In denial of all time-preference, dollar interest rates held at zero have the same effect. The only way the disposal of deposits for unneeded goods can be slowed is to allow a market-determined rate of interest to return. Given the widespread and growing expectation that the dollar’s future purchasing power will decline, interest rates will undoubtedly rise — a process that may have already started with the 5-year Treasury yield having more than doubled to 0.46% since early August.

It should never be the function of a central bank to replace markets in setting interest rates, because only economic actors can decide them between themselves. For savers it is the time preference they require and for borrowers their calculations of acceptable financing costs. By manipulating interest rates lower over time, central banks have entrapped their governments into the expectation of infinite interest-free money. Consequently, when interest rates finally begin to reflect the time preference of an inflating currency, they will impose enormous losses on bond holders and materially increase the expense of inflationary funding of the budget deficit. At first, it is likely that foreign holders of dollars will force this issue.

The alternative, cuts in government spending, will become progressively more difficult politically to achieve, so long as the government sees its duty as being to support the economy by providing it with yet more money, extracted by debasing the currency at an ever-increasing pace. The neo-Keynesians never accept that the solution to the inflation problem is to radically cut government spending in order to stabilise the currency, until it is too late.

The speed of monetary collapse

Of the known hyperinflations there has been considerable variance in the speed with which a currency loses its purchasing power. In 1720, John Law’s livre collapsed in a little less than a year. The paper mark in Germany began to noticeably lose purchasing power in the post war years, but its final collapse started in about May 1923 and was set at a trillion to one gold mark on 14 November.

In the later stages of Germany’s inflationary collapse and when it became difficult to conduct business in paper marks, businessmen turned to gold-backed foreign currencies. That some business was conducted by these means improved business conditions above a level relative to where they would otherwise have been if all business was conducted in paper marks. Export business was profitable and led to remittances in foreign currencies, building the stock of foreign currencies in domestic circulation. Instead of being wholly dependent on paper marks, business transactions and contracts were increasingly conducted in foreign currencies or in paper marks contracted at a predetermined rate relative to dollars or gold.

The growing level of business avoiding the use of the paper mark alleviated it from some of the pressure leading to its collapse. The time taken for its collapse was therefore lengthened, compared with a situation where gold and foreign currencies were absent. A current example of this duality can be found in the rate of loss of purchasing power in the Argentine peso and Turkish lira, currencies which continue to exist in economies with significant levels of transactions conducted in US dollars and gold respectively.

The situation with the US dollar itself is different. It is the world’s reserve currency, not backed by anything other than faith in its issuer, a condition which must also apply to all other currencies that use dollars as their principal reserve asset. Other than gold, there is therefore no alternative sound money available in the event the dollar is rejected by its users. Therefore, the US economy and that of the whole world is exposed to a collapse of the dollar’s purchasing power which, in the absence of an alternative medium of exchange to delay the process, could be surprisingly quick.

The way this outcome could be averted is by putting the dollar back on a credible gold standard, almost impossible given the likely time constraint of a rapid collapse. America claims to have over 8,000 tonnes of gold in its reserves, with which it could back the dollar. To do this it would have to deliver its gold reserves to the direct ownership by the Fed, so that the Fed could settle transactions in gold, and a gold-dollar exchange rate decided. That should be the easy part. More difficult would be the withdrawal of the US Government from its spending commitments so that it could service and repay its debts over time.

The Keynesian macroeconomics that give universal credence to inflationism is the greatest obstacle to a successful return to monetary stability. Any policy of stopping inflationary financing of deficits is likely to meet overwhelming resistance from all quarters of government and their economic advisers. They would be more likely convinced of the benefits of eliminating the burden of accumulated Treasury debt over prioritising monetary stability.

Furthermore, so far as the establishment is concerned, metallic money is money no longer. The re-education of central bankers and their economic advisors about money is only likely to happen in the wake of a complete breakdown of the dollar’s purchasing power. But a monetary collapse in a financially driven economy would be catastrophic not just for the financial system but for the people themselves, because unlike the situation in Germany eighty-seven years ago there is no alternative in which to conduct business and settle transactions.

The replacement for fiat currencies

It would therefore appear that the most likely outcome of the accelerated rate of today’s inflationary policies will be to hasten the demise of the current fiat money regime, centred on the US dollar, and that once the American public awakens to the fact that it is not prices that are rising but the purchasing power of the currency falling, the end of the dollar and all associated fiat currencies is likely to be swift.

It is impossible to forecast when the collapse of the fiat currency will happen, other than to note the factors involved. Since the unwritten objective of monetary inflation is to transfer wealth from the people to its government, an acceleration of the process requires far-sighted individuals to take urgent action to protect themselves instead of becoming victims of unfolding events.

The two options available are the established metallic monies, to which over the millennia people have always returned following the failure of state-imposed currencies, and crypto currencies. Crypto currencies may have hastened the end of fiat currencies by educating important sections of the public about the consequences of monetary debasement, which they now observe accelerating. This development itself threatens to radically escalate the speed with which public trust in fiat fails, and binds the faithful to crypto currency concepts.

The cheerleader for cryptocurrencies is bitcoin, whose ledger is beyond the control of governments. Other than its distributed ledger, the principal quality is that its quantity is capped, giving it an important characteristic of sound money. A disadvantage is it will need additional layers of often opaque applications to enable large volumes of transactions. But for the moment, bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies offer an escape route from the debasement of fiat currencies.

While being an effective store of value so far, bitcoin’s volatility makes it unsuitable for use as transactional money, because a medium of exchange requires it to have an objective value, so that all pricing subjectivity is reflected in the goods and services being exchanged. And without this objective value it is also unsuited for the role of capital in business calculations.

This is the current situation from which events will evolve. On the demise of fiat currencies, the objective value of bitcoin must then either be applied to transactions of goods in accordance with Say’s law, or alternatively be subjectively priced in metallic money. The question being considered is will the quantity-limited bitcoin emerge as the new monetary standard, or will the world return to a relatively more flexible gold standard, evidenced by mine supply and the circulation of gold coins?

The basic principles of money must be restated to answer this question. The use of money is firmly bound to the division of labour. The role of money, from which all its secondary uses are derived, is to enable producers to turn their production into the goods and services they require. As the temporary storage of their production, money must give certainty to its future value measured in goods. Without that certainly there can be no economic calculation. It allows those who defer their consumption to do so and to estimate a time preference, while a borrower can calculate the cost of monetary capital as part of his production plans.

As currently constituted, no cryptocurrency can act as a medium of exchange which satisfies these objectives. They are not sufficiently endowed with the money qualities to replace metallic money and their fully backed substitutes as the world’s post-fiat currency. Gold and silver are already widely distributed in some economies and can emerge rapidly for monetary use. Governments have stocks of gold which will enable them to issue gold-backed substitutes assuming they get over their Keynesian hang-ups. These conditions being the case, in a post-fiat world it can be assumed that cryptocurrencies will be priced in gold after fiat, with gold having the objective transactional value and crypto the subjective. Therefore, only gold and silver and their credible substitutes can re-emerge as the principal form of sound money.

At that point, the store of value function of cryptocurrencies will become redundant, and the need for them will cease. As a store of value before fiat currencies are finally discarded by their users, cryptocurrencies may continue to offer protection against fiat debasement, and the cryptocurrency industry can only hope that fiat money is never actually destroyed and gold backing of them continues to be rejected.

But the continued existence of unbacked fiat is rapidly diminishing as a possibility. Gold and silver will therefore re-emerge as money. Individuals seeking an early shelter in sound money should regard them as such and abandon the common fallacy that they represent an investment. An investment is a hedge against possible events, always to be valued in fiat currency, a component of a portfolio of fiat-denominated assets. But an investment is never money, because money has the objective value against which investments are measured.

It may be easier to adopt this way of thinking by discarding the belief that inflation is an increase in the general level of prices. That is merely the symptom of a currency debasement. Understanding why the government resorts to debauching its currency, the certainty of its eventual failure, the signposts along the way to its demise and acting early instead of reacting to events, are all the key to surviving the annihilation of fiat currencies.

[i] See https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CONSUMER

By Alasdair Macleod, www.goldmoney.com

Find more: Contributing Authors