A primer for gold newbies

The purpose of this article is purely educational. Increasingly, the wider public is turning to gold in a spontaneous reaction to financial and economic problems that have become suddenly apparent, hastened by the spread of the coronavirus. For everyone now thinking of buying gold it is a leap into the unknown, so they should know why.

It is not just the financially inexperienced, but investment managers and financial advisors are equally unaware of what is happening to money and capital markets. We are in the early stages of a radical debasement of state-issued currencies which is on course to collapse the entire financial system.

I explain the two phases of this destruction of fiat money, the one experienced so far and the one we are about to suffer. I explain why sound money has always been physical gold and silver, returned to by the people after government and banks have collectively destroyed state-originated unsound money.

Introduction

Suddenly, there is increasing public interest in gold. The financially aware will be scratching their heads over what’s going on in financial markets in the broadest sense and might have heard some unintelligible chatter about what is going on in gold. They are asking, why does gold matter? Isn’t gold just an old-fashioned hedge against risk and the true safe haven investment today is US Treasuries? Then there’s the mass of financially unknowledgeable investors who are used to leaving investment matters to their financial advisers, and until recently have viewed the rise in the gold price as an opportunity to sell unwanted jewellery for scrap.

In these two categories we have included the bulk of the population of any advanced nation. They are about to learn what less sophisticated peoples never unlearned: that there’s a difference between a world that is accustomed to relying on ever increasing public debt to provide their welfare, and one where the state provides little or no welfare and people must save to provide for their own and their families’ future.

In Asia, the cradle of civilisation, gold and silver for millennia have had a dual role of ornamentation and of sound, reliable money which can be safely stored for future use. It is only in the last two centuries that the people of Britain, and then America, have advanced themselves into consumerism and taken many other nations with them, leaving the rest of the world described as emerging nations, a euphemism for still poor and uncivilised in western terms.

That is no longer true. In the four decades since Mao Zedong’s death, China and the whole of South-East Asia have embraced debt-fuelled economic progress. Following the end of the short-lived Gandhi era, India is similarly progressing. And when economists forecast global growth, they expect it to come predominantly from these Asian nations while the West stagnates.

Even though these Asian nations have now almost fledged, their populations still save a substantial portion of their income and profits, savings which are the security for their future. While they have embraced inward investment from western and Japanese corporations building factories and providing employment, they hang onto their savings, which are mainly in gold and silver, to preserve their families’ wealth.

For example, it has served the Indian peasantry very well. The price of gold has risen from 180 rupees to the ounce in the mid-1960s to 121,000 rupees today. Of course, it’s not so much gold going up, but the rupee going down. Ordinary Indians have retained the wisdom of their ancestors, despite attempts by successive governments to ban or discourage them from junking rupees by buying gold.

Whatever you believe, the economic awakening of Asia means you can no longer ignore gold and silver’s historical role as the ultimate money. In terms of personal savings, we are faced with a radical re-think because our currencies are demonstrably on the brink of failure. The current dollar-based system evolved from gold standards to a partial gold exchange standard following the Second World War, to abandoning gold backing entirely in 1971. Now, investors are having to learn the gold story anew, exchanging their western debt-driven economics for a world that is reverting to gold.

For the West’s financial establishment, it will be a difficult and costly process. Investment managers’ careers have unwittingly depended on a form of money that is continuously debased, because their performance is enhanced by its loss of purchasing power. Take monetary inflation away, and it is no exaggeration to say the business of purely financial assets, that is to say bonds, equities and derivatives, will mostly disappear.

The sudden relevance of this outcome has been brought to all our attentions by the coronavirus pandemic. The panic currently raging through markets is leading directly to infinite acceleration of monetary inflation, because it is the only means for governments and their central banks to postpone a financial and economic crisis. We are witnessing the early stages of a fiat currency collapse due to its unlimited and accelerating debauchment in an attempt to preserve the West’s financial system.

On any dispassionate analysis, throwing limitless money at a problem is a matter of desperation that ends with the destruction of the currency. For the common man it eventually raises hitherto unasked questions: is the state’s money really money? Should I hold a reserve of it so I can buy the things I will want tomorrow, or should I spend it all now just to get rid of it?

It is this background that causes the wider public, not the financial establishment that hitherto has benefited from monetary inflation, to reconsider gold as a safe haven against mounting uncertainties. Physical possession, or having gold vaulted securely is suddenly becoming preferable to having money invested in a financial system evidently on the brink of failure. Forget investment managers, economists and their economics, it is now time for everyone for himself and his or her dependants.

It is therefore time to relearn the fundamentals about gold, and silver for that matter, in their role as sound money. If anyone is to emerge financially intact from a financial and monetary collapse it will be by hoarding sound money to spend frugally when the time comes.

The aim of this article is to help those who have been seduced by inflationism and lost touch with sound money to regain it.

Why gold and silver are always money and why fiat is failing

From the dawning of economic history various forms of monetary intermediation have been tried. The only ones that have survived the test of all time have been metallic, particularly copper, silver and gold, because of their durability. They evolved from being measured by weight into being unitised as coinage.

As the principal issuer of coins, the state gained a monetary role, and could collect taxes in token coins more efficiently than through the payment of tithes. And with the state controlling the form of money came state corruption. The Chinese were the earliest recorded issuers of paper money, and Marco Polo related how Kublai Khan required merchants to submit all their gold and silver in return for paper receipts manufactured from mulberry leaves. The merchants gained the experience and Kublai Khan got their money.

The Romans robbed their citizens by debasing the coinage, starting with Nero who used the surplus silver thereby gained to pay his army, a tradition that continued with succeeding emperors. It was a failed policy, with assassinations being common. Debasement continued for nearly three centuries to the time of Diocletian, who tried to control the effect on prices through his infamous edict written in stone. The economic consequences of the collapse of Roman money together with price controls led to citizens abandoning the cities to forage in the countryside, a feature of other monetary collapses we have seen time and time again.

With the collapse of fiat currencies today, these outcomes should be borne in mind. But there is another form of monetary fraud to be aware of, poorly understood, which involves the banks. From the earliest times of recorded history, bankers would take in deposits for safe-keeping and redeploy them for their own use. In about 393 BC, an Athenian lawyer, Isocrates, defended Passio, a banker accused of misappropriating deposits of gold and silver entrusted to him by a son of a favourite of Satyrus, king of Bospherus. While Isocrates’s speech is recorded, it seems the verdict is lost to us. But like so many bankers who followed him, Passio survived the scandal and died a wealthy and successful man.[i]

The misappropriation of deposit money has been a feature of banking ever since, and today’s denial of the fundamental right to own your deposited money was formalised in the Bank Charter Act of 1844 in English law, which failed to differentiate between actual banknotes that were backed by gold, and money loaned into existence by fractional reserve banking, which become the source of customers’ deposits.

To further expand the point, we must briefly digress and describe the process of creating bank credit and matching deposits. The common procedure is for a bank to create a loan facility for a customer, who draws on the facility to pay his creditors. The creditors then have money to deposit, which is either deposited at the bank that originated the loan or at another bank. To the extent that loans drawn down create imbalances between banks, they are resolved in wholesale money markets so that all banks’ balance sheets balance. But note that the money loaned created the deposits, and it is by these means that banks create unbacked money in a system supposedly on a gold standard.

Fractional reserve banking is so described because the ability to create deposits by loaning money into existence allows banks to gear up their balance sheets so that their own capital becomes a fraction of the total. At any one time the relationship between the two reflects the bankers’ assessment of risk and reward. At times of low perceived risk and improving economic prospects, they expand the ratio of deposits and other liabilities to ten or more times their underlying capital. When they perceive increased lending risk, they try to reduce the ratio to prevent their capital being wiped out by losses.

The economic consequences are periodic banking crises as banks become first overextended and then ultra-cautious in their lending. Additionally, there is the response by governments and their state-owned central banks to the periodic banking crises, in which they intervene rather than let banks fail.

It was Walter Bagehot who in the late-nineteenth century coined the term for the Bank of England acting as lender of last resort, a function which has become more extensive over successive credit cycles. The quantities of bank credit have expanded over time and the accumulation of money issued to finance periodic bank rescues and excess government spending has remained in the system. Inevitably, it led to the abandonment of any pretence of backing state-issued currency with gold when the gold pool failed in the late 1960s.

When the relationship between gold and state-issued currencies finally broke down it permitted monetary inflation, whose only constraint was the effect on prices. This brings us to the current situation, where the expansion of the quantity of money in all major currencies is about to increase massively, in an attempt to control the economic consequences of the coronavirus.

Unlimited monetary expansion became stated official policy for America’s central bank last week and stated or unstated, for the other major central banks as well. The implied monetary policy was that as soon as the virus passes the economy will return to normal, so the monetary expansion will normalise.

But it should be noted that liquidity strains in the banking system began to be appear last September, nearly five months before the virus spread from China. The Federal Reserve Board (America’s central bank – the Fed) was forced to begin a daily series of monetary injections into the banking system, which is ongoing. Liquidity problems are simply a sign of fractional reserve banks perceiving a shift in the balance of profit relative to risk and acting to protect their capital from losses. Put another way, the liquidity shortage is created by banks destroying money by reversing the bank credit creation process.

Therefore, the evidence that the credit cycle has turned cannot be disputed and will add to the required quantities of money to be issued by central banks in connection with the virus alone, if a deflationary contraction of bank credit is to be averted. It is beyond the scope of this article to go fully into what will be involved, but the scale of monetary inflation required is clearly immense.[ii]

What will alert the public to failing fiat currencies?

Statisticians inform us that the rate of price inflation is in the order of two per cent. All our personal experiences suggest it is much higher, and independent analysts in America tell us it is closer to ten per cent, more in line with our own knowledge than government figures. The discrepancy exists because we can talk about the general level of prices as a concept, but that does not mean we can actually measure it.[iii]

This is important, because the cost of funding government borrowing (and everyone else’s for that matter) is linked to the rate of price inflation. Buyers of US Treasuries, regarded in financial circles as the risk-free investment, will want a rate of return to compensate them for the loss of the dollar’s purchasing power over the life of the investment. For now, they accept it is a little less than two per cent annually as stated by government statisticians, but that is bound to be questioned when the Fed ramps up its money-printing.

So far, most notably the expansion of money supply has fuelled rising prices for financial assets. That inflated balloon in now leaking badly. When doubts increasingly begin to creep in about a realistic value for all bonds relative to a realistic assessment of price inflation, all financial assets that refer to US Treasury bonds as the risk-free yardstick will deflate even further. Consequently, investors accustomed to more or less continually rising prices for financial assets will face substantial losses. The penny is now dropping that investing in them for wealth preservation is unsafe, and the central banks’ policy of debasing money to support financial markets will eventually fail.

In another development, the US Government has just passed a reflation bill whereby each qualifying adult will be given $1200 and $500 on behalf of every child. This money can only be spent on essentials such as food, because the majority of retailers are in lockdown. Meanwhile the production and distribution of food is likely to be adversely affected by the virus. There can be only one outcome from the combination of a restriction of food supply and a one-off hit of extra money for everyone: prices for food will rise strongly. Following the example of Diocletian’s edict, we can then expect politicians to impose price controls in an attempt to quell public dissent, which will inevitably reduce food supplies even more.

Never mind what the consumer price index says; food is a small part of it and officially, the CPI might even fall. But a growing likelihood of public disaffection over food prices is bound to spread the message that the dollar is not buying as much as it did very recently. It is a small step from there for the American public to finally reject the fiat dollar as a medium of exchange. We will then learn a fundamental truth the hard way: money relies on its credibility with the people who are its users. And once that credibility is destroyed the currency is destroyed with it.

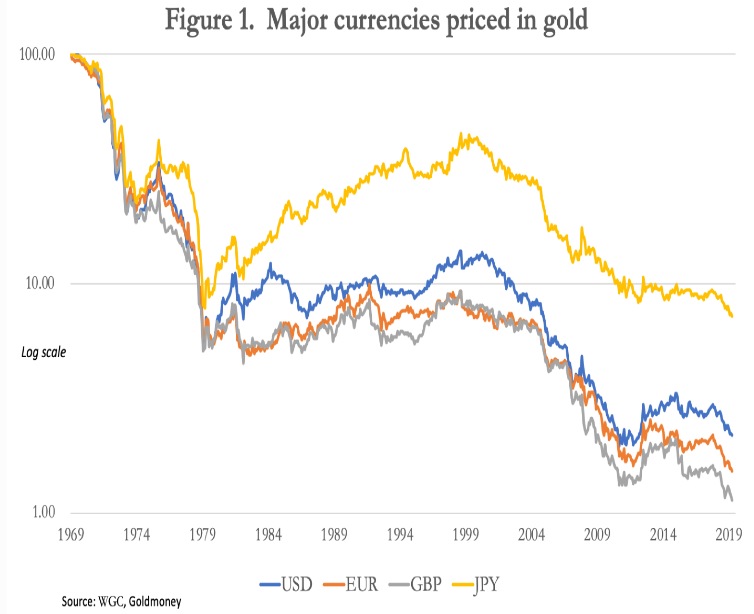

The time taken for its destruction has been illustrated by similar events in the past. We must distinguish between a long, slow cumulative attrition of value, such as that since the failure of the London gold pool in the late 1960s, followed by the ending of the remaining fig leaf of gold convertibility by President Nixon in August 1971. This is the first of two phases, illustrated in Figure 1.

Since 1969, relative to gold the yen has lost 92.8% of its purchasing power, against the dollar 97.8%, the euro (and its previous constituents) 98.5% and sterling 98.9%. And these falls have been hardly noticed! As the yardstick for sound money, gold has been deliberately side-lined in favour of the dollar as the backing for other fiat currencies. When the British think the pound has fallen, they say it is against the dollar, oblivious to the fact that the dollar itself has lost all but 2.2% of its 1969 purchasing power.

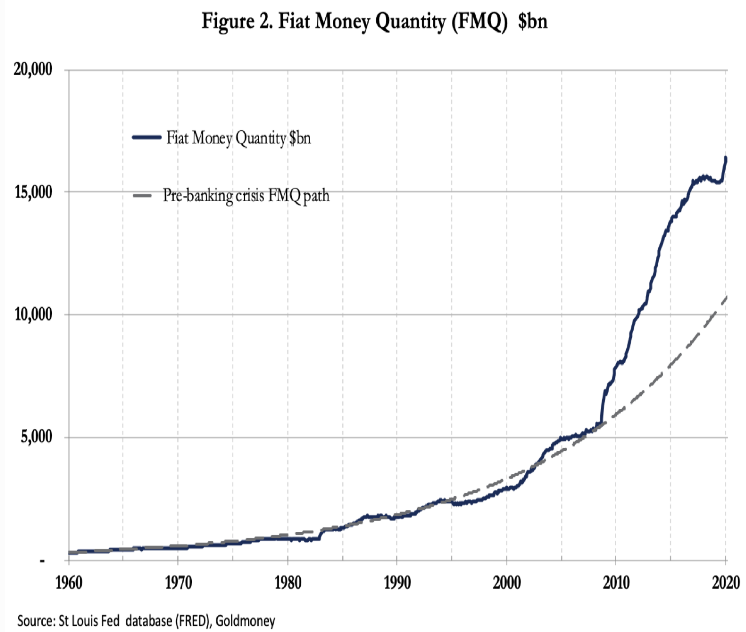

The reason behind the dollar’s decline is the massive expansion of the quantity of dollars relative to gold, shown in Figure 2.

The fiat money quantity is the total number of dollars both in public ownership and held in reserve by the banks in their accounts at the Fed. Because these figures are only available six weeks in arrears, they have yet to reflect the most recent expansion of money. But it was already shooting into record territory at the beginning of February and the extent of monetary instability is illustrated further by its departure from the relatively steady expansionary course until the Lehman crisis, shown by the extended pecked line.

The expansion of FMQ from 1969 has been a multiple of 32.5 times, giving an arithmetic dilution of purchasing power of 97%, which compares with a fall in terms of the gold price of 97.8%. We can therefore say that over fifty-one years, the change in the dollar price of gold has tracked the expansion of the quantity of dollars as represented by the fiat money quantity fairly accurately.

Empirical experience tells us there is a second phase, when a broadly arithmetic relationship between the quantity of money in circulation and its purchasing power breaks down. When the public awaken to what is happening to fiat money, a mass psychology of rejection takes over to drive the relationship between the currency and its use-value. In France, the mandats territoriaux issued in February 1796 to replace the failing assignats currency were worthless by the following February. In 1923, the German papiermark, which had been losing purchasing power from the end of the Great War took about seven months to finally collapse from May to November. It became a flight into goods and real values that marks the end of a monetary inflation by the complete breakdown of the monetary system.

For a comparison with the contemporary monetary system, which binds together the fate of financial asset values and that of the currency, there is none more apt that that of the failure of John Law’s Mississippi bubble, when he gained control of the French currency and printed it to support the shares of his venture. Law’s policies of inflationism were remarkably similar to those of John Maynard Keynes, which inform the basis of monetary policy today. And today’s neo-Keynesians are unashamedly debasing the currency to support financial assets, just as Law did. Law’s scheme began to show signs of failing in early 1720, and by the following September, not only had the shares in his Mississippi venture collapsed, but his unbacked livres were worthless as well.

If we replicate the John Law experience today, the dollar and all the currencies which sail with her will become worthless in short order, probably by the year-end. We have seen that a final acceleration of monetary inflation is starting after a fifty-year period of debasement which the public has hardly noticed. State-issued fiat currencies are now embarking on that second phase, when they will lose all purchasing power.

The replacement of government fiat money by gold and silver

Now that we can anticipate the final destruction of contemporary fiat currencies, we must consider their replacement and how it comes about. Many commentators who have a grasp of the problem talk of a monetary reset, failing to understand that the problem is a loss of trust in state-issued currencies that cannot be resolved by the issuance of a variation on the fiat theme. Nor can a solution be found in the issuance of a state-issued cryptocurrency. The fact of the matter is the days of financing government spending and economic objectives by monetary expansion are drawing to an end.

A few governments are in a position to back their currencies with gold, freely convertible at the choice of the user at a fixed rate. These include Russia, which has been accumulating gold and dumping dollars in recent years. China, where there is compelling evidence that the state has accumulated significant undeclared bullion, and now that an estimated 17,000 tonnes are in private ownership, could also adopt a gold standard, along with a few other Asian nations. But a gold standard also requires the elimination of government spending deficits, which Russia, China and a few Asian nations could achieve. Additionally, the banking system, whereby bank credit can be expanded by creating loans, must also be reformed. Otherwise, it will be possible for anyone to draw down a loan in unbacked bank credit in order to cash it in for gold. Similarly, safeguards to prevent foreign bank credit expansion being used through the foreign exchanges to acquire gold substitutes for encashment would have to be implemented.

Western nations will find it far more difficult to adjust to a gold standard, having mandated welfare commitments that require continuing currency debasement in order to pay for them. Furthermore, in the United States, the banking cartel is immensely powerful and so long as the fiat system exists, they are unlikely to give up their assumed right to create money out of thin air in the form of credit, particularly when the process becomes more profitable as the dollar’s decline accelerates. The currency will therefore die before radical reform is acceptable to the US financial establishment, and all those that adhere to it.

For individuals, it is safer to assume that personal possession of physical gold and silver bars and coins is best for wealth protection and future spending. It is a mistake to think that these two moneys of millennia are just an investment alternative: they are money which can act as a store of your wealth. They can then be spent on the essentials of life, which are spiralling beyond the reach of failing fiat. And when the return of some economic and political stability can be anticipated, durable assets, such as property, and productive goods might be acquired. In that way gold and silver will return into circulation.

The failure of derivatives

Derivative markets, principally Comex futures and the London bullion market, have expanded to absorb much of the demand for bullion. Taken together, the last recorded figures tell us that gold derivatives in these two markets had a notional value of $600bn, while the sum of annual mine production and recycled scrap at the same time was worth approximately $20bn, a relationship of 30:1.[iv]

As argued in this article the acceleration of monetary inflation is collapsing both financial markets and fiat currencies. What no one tells you is that over-the-counter derivatives, which according to the Bank for International Settlements are worth $640 trillion, will also disappear in a fiat currency collapse. Therefore, assuming there is no change in the overall level of demand for gold, thirty times the level of physical demand previously accommodated in derivatives at end-June last year either disappears or will be accommodated in above-ground stocks of gold.

It is in that context we should interpret what is happening in financial markets. The strains at a time of contracting bank credit are acute. If they have not been told already, dealers at the bullion banks will be instructed by their financial controllers to reduce their positions, because of the inexorable pull of contracting bank credit in the bank’s wider lending and deposit activities.

The only avenues for acquiring exposure of gold and silver will be increasingly restricted to bullion itself. Retailer outlets have already been closed by the virus and online retailers have little or no stock. Gold and silver can be acquired through companies such as Goldmoney, so that personal wealth can still be stored in secure, insured vaults. Physically backed exchange-traded funds continue to be available, but with the increasingly certain demise of derivatives, and the problems likely to evolve for the ETFs which use them, ETFs backed by physical gold are also exposed to unforeseen issues.

The hiatus on Comex probably marks the beginning of the end of precious metal derivatives. Already, bullion banks have reduced their exposure on Comex by the equivalent of 938 tonnes to 1,541 tonnes. But with supply substantially reduced from mines and refiners in lockdown at a time when governments are promising unlimited monetary inflation, it is hard to see favourable conditions for an orderly wind-down on Comex.

Conclusion

Events over the last few weeks have alerted a wider audience to the destruction of values in financial markets. The unwritten agreement between investors and the major central banks whereby financial markets will always be supported is now unravelling. Increasingly, the only buyers of government bonds at current levels are the central banks by inflating their currencies.

Meanwhile, liquidity problems in hard-hit economies are mounting. And it is not just the coronavirus; nearly five months before the virus hit Western financial markets the Fed was having to inject liquidity into the US banking system in record amounts through the repo market.[v]

Looking at historical comparisons of our current set of circumstances we find that the Mississippi bubble of 1720 in France appears to be a reasonable template for the current situation. John Law, who masterminded that scheme, gained control of France’s money which he then used to buy shares in his Mississippi venture. Today’s central banks are following a similar path, except on a global scale. Law’s scheme saw both his unbacked currency and the shares in his Mississippi venture collapse from top to bottom in only nine months. If we repeat this experience today, not only will financial markets collapse, but the currencies in which they are notionally measured will be worthless by the year-end.

Signs of failure in some markets, such as derivative markets for precious metals, can be taken as evidence that a wider financial dislocation is now in progress. It is in this light that an understanding of the role of physical gold and silver is so important. They are the only sound money, a safe refuge for ordinary people, being incorruptible by governments. And as their prices rise towards infinity, it will be entirely a reflection of the end of the current fiat money regime.

[i] The story of Passio is recounted in Jesus Huerta de Soto’s Money, Credit, and Economic Cycles Chapter 2.1. De Soto also recounts instances of banking practice and failures in Ptolemaic Egypt and Rome.

[ii] For further explanation of the likely extent of monetary inflation, see https://www.goldmoney.com/research/goldmoney-insights/payments-panic-and-the-ending-of-fiat-currencies

[iii] See Chapwood.com and shadowstats.com.

[iv] As at end-June 2019, when the gold price was $1387. Data from The Bank for International Settlements, Comex and the WGC.

[v] In a repurchase agreement (repo) a bank swaps high quality collateral for cash for a defined period, after which the swap is reversed. It is a mechanism to give the bank short-term liquidity.

By Alasdair Macleod, www.goldmoney.com

Find more: Contributing Authors